Can We Know When We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know?

Years ago I visited a spa where 4 magnificent macaws stood on individual perches, each with a long, not necessarily heavy, chain around one of its legs. Yet the chains were not attached to anything: if the birds had known what they didn’t know, they could have easily flown away.

Years ago I visited a spa where 4 magnificent macaws stood on individual perches, each with a long, not necessarily heavy, chain around one of its legs. Yet the chains were not attached to anything: if the birds had known what they didn’t know, they could have easily flown away.

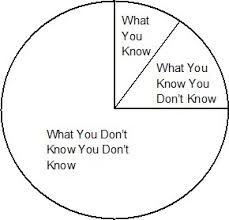

I was reminded of that recently when sitting with a close friend starting up a company. I suggested he write down 1. What he knew he knew; 2. What he knew he didn’t know; 3. What he didn’t know he didn’t know (This being impossible, but the column needed to be there as you’ll see.). A long-time friend, James was always up for my mischief. He promptly began writing a list of what he knew that he knew. As I looked on, knowing him as long as I did, I noticed two items I knew for certain he did NOT know.

I told him I had doubts about some of the items he thought he knew and that they belonged in the ‘don’t know that I don’t know’ column. I asked him how he’d know if thought he knew something but in fact was mistaken.

“Oh. I guess there’s no way to know unless I fail. Without knowing there’s any other option, I wouldn’t even know when I need help or the kind of help I needed.”

A similar situation came up recently when a colleague explained how his sales team ‘truly cared’, and ‘truly served’ prospects. When I asked him what skills he was using to care and serve, he rattled off the same skills he used when selling. And even though we’d known each other for some time and he’d read a couple of my books, it never occurred to him to contact me to learn additional skills he knew I’d developed specifically for what he was doing. Why? Because his results were ‘wildly successful’ – a close rate ‘higher than others’ (10% success vs 5% industry standard – but still a 90% failure). He never stopped to consider that he could have been much more successful with additional skills. He didn’t know what he didn’t know.

OUR BRAIN

So how do we know when we don’t know what we don’t know? We don’t even know how to think or consider something outside our assumptions or beliefs, or something not already in our neural makeup. There’s just no way to know what outcomes, risks or rewards, skills, comparators, or thought processes are possible. So how do we attain the courage to do something different when we have no way to even think about it?

Let’s consider how we do anything at all. Our brain instigates our actions, thoughts, what we hear, how we decide and choose, how we behave. When we have an idea or goal, hear a lecture or are given a directive, our brain

- receives and filters (some deletion involved) incoming vibrations – words being meaningless puffs of air until our brain translates them – and

- turns them into electrochemical signals that

- get sent down well-worn pathways (superhighways) that

- lead to existing, ‘similar-enough’ circuits (some deletion involved) that

- instigate habitual behaviors and outcomes.

In other words, whatever we think, hear or read enters our mind as sound vibrations that end up being (mis)translated through some conglomeration of synapses, pathways, circuits, etc. and we end up ‘hearing’ little more than something we have previously experienced, regardless of the facts. And our brain doesn’t tell us what havoc it’s played: we just assume what we think we heard is accurate.

I was once meeting with a couple who were licensing some of my material. I made a comment that John interpreted what I said as X when I actually said Y. I carefully explained, again, what I’d said. Here is what followed:

John: You didn’t say that! I heard you say X with my own ears!

SD: No, John. You misheard. I said Y.

Wife: John – she really said Y. I was standing right here. You heard her wrong.

John: YOU’RE BOTH LYING!

And he stomped out of the room, and never spoke to me again.

Listening is a brain thing, causing us to interpret incoming sound vibrations according to where among our 100 trillion neural circuits the sound vibrations get sent. [See my book What? Did you really say what I think I heard?] Indeed, we hear some rendition of what a Speaker means to say, and rarely ‘hear’ accurately. Let me explain.

The way our brain turns signals into behaviors, ideas, or thoughts, determines everything we hear, think, and do. Usually it’s a good thing. It’s how we know to get up in the morning, put our slippers on, and brush our teeth. It’s how we make our decisions, go on our diets, make our New Year’s resolution. But it’s restrictive. In fact, and I still get annoyed about this, our brains automatically pretty much keep us doing what we’ve always done and we have very little say in the matter.

Indeed, we live our lives restricted and directed by how our neural circuits translate for us. And certainly, that provides a lifetime’s worth of choices. But: our curiosity, our ideas, are restricted by what’s already there.

I’ve developed a model to make it possible to change habits and behaviors by consciously adjusting your unconscious hierarchies and neural pathways. It includes wholly new skills, tools, and thought process with a hands-on learning and Belief change process.

Can we know what we don’t know that we don’t know? Because when we can’t, we’re left with the results of fewer choices with no way to know what to look for if we need to add something new.

WHAT’S IN THE WAY OF ENCOURAGING ‘NOT KNOWING’

Don’t get me wrong. none of us ever intends to mishear, or misunderstand, or restrict ourselves. But we’re basically out of choice, never told what our brain has edited or deleted, or what other choices were possible if our brain chose different circuits to translate the incoming vibrations.

Let me share my thoughts on some of the reasons I think people have a hard time getting beyond what they know (or don’t know they don’t know):

- Ego. People have a hard time acknowledging they are ‘deficient’. I’m not sure why. My question is: “What would stop you from seeking assistance at those times you’re aware that you are missing knowledge? Those times you have a pattern of failing and have no additional options?”

- Assumptions. When we presume we know something, we have no reason to think differently. Unfortunately, when failure occurs we have a ‘blame’ response since we, obviously, can’t be wrong and the Other, obviously, must be the culprit. Entire fields are based on Others being wrong because they don’t heed the provider (healthcare, sales, coaching, etc.).

- Denial. Wrong? I’m not doing anything wrong. Better? I already know how to do that. I really don’t want to change. I know my stuff is better. Why should I want to know what I don’t know when I already know what’s best? Sometimes people prefer their own ideas and ignore incoming content that would lead them to greater success.

- Listening Bias. Sometimes we are so committed to a specific outcome and approach that we consider successful that we listen to others through very biased ears and allow our brain to tell us what we want to hear…without question. I try to avoid this by seeking answers from people from different industries, or countries. But when we enter a situation with the end in mind, whatever we hear, whatever we take away, will be biased by our history.

- Fixed Views. We become attached – both emotionally and neurologically – to what we know. With a habituated superhighway that leads us straight to oft-used answers and beliefs, we dislike going through the decoupling process to accept and adopt a new answer.

Net net, due to our lazy brain and idiosyncratic personalities, there’s no way to naturally recognize when we don’t know what we don’t know. This makes it quite difficult to learn anything new until we fail and it becomes obvious.

HINTS

Here are a few ideas that might lead to more choice:

- When you face confusion, it’s because your brain’s dispatch unit (the Central Executive Network) can’t find an existing set of circuits to translate or interpret new ideas – a perfect time to recognize there’s something you don’t know.

- When you’ve had repeated failure, there’s something you’re missing. What needs to happen for you to get curious? Assume there are better answers somewhere?

- Ask others who know more than you do. Here is where a good friend or coach comes in. People who are outside your field will ask questions that you may not have answers to. And you need to find them!

- Research. When I’m developing a new model I do broad research – reading sample chapters or whole books on unfamiliar topics (Picking Up by Robert Nagle about the New York City garbage collection provided new ideas about systems), researching papers and articles on topics adjacent to my ideas – to find new concepts that I hadn’t heard before to stimulate further thinking. I’ll never forget how my world shook when I learned that no input (no ideas, words, sounds) could be interpreted outside the circuits I have in my brain already. That upset me for a week! And it absolutely shifted my thinking.

Entire fields are missing information and doing nothing to discover what they don’t know:

- Healthcare professionals don’t know why patients ignore their directives. For instance, handing someone a new food plan without them knowing how to change habits and neural circuits congruently will instigate resistance. Instead of doctors blaming themselves for not knowing how to facilitate congruent change, they blame patients for not having motivation.

- Coaches, managers, leaders, supervisors assume their mandates will be followed. Clients who don’t follow them are said to ‘not really want to change.’ At no point do they acknowledge that their approach may be the problem.

- Sellers and marketers continue to push solutions, overlooking the way people actually buy and face lower and lower success rates (now 5% rate) that should alert them there’s something they don’t know. What other industry believes that a 95% failure rate is ‘success’?

- The training model fails 80% of the time. Pushing new content into a brain that might not have circuits to translate it accurately causes confusion, resistance, and disregard causing trainers to assume learners are ‘unmotivated’. Learning how to design programs that generate wholly new circuits for the new knowledge is not anything instructional designers know they need to know.

- Business Process Management uses a flow chart that invites front line workers into the process halfway through the flow! Obviously this leads to implementation problems, such as insufficient data collection and resistance when people are pushed to be compliant against their will. One of the leaders in BPM recently approached me about adding the Steps of Change (a model I invented that facilitates the flow of change and decision making) to help them, but he became agitated when I suggested he needed to begin at Step One by assembling everyone who touches the problem. He left our discussions, not realizing he was following the exact failed format he called me to change.

- OD and Change management relies on standard questions which are biased and restricted by the thoughts of the asker – and ignore the foundational Beliefs and norms that shift in the Other’s brain for congruent change to occur. And they don’t question why they get resistance, time delays, lack of buy-in. They just blame the Other.

So I leave you with these questions:

– How committed are you to having the full set of data you need for success?

– How willing are you to forego your ego and Not Know?

– What would you need to know or believe differently to recognize when you don’t possess the full data set you need?

Imagine how successful we could all be if we knew what we didn’t know and had the right attitude to find out.

___________________________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen February 6th, 2023

Posted In: News