Beyond Empathetic Listening

We all know the importance of listening; of connecting with others by being present and authentic to deeply hear their thoughts, ideas, and feelings. We work hard at listening without judgment, carefully, with our full attention to connect and respect.

We all know the importance of listening; of connecting with others by being present and authentic to deeply hear their thoughts, ideas, and feelings. We work hard at listening without judgment, carefully, with our full attention to connect and respect.

But are we hearing them without bias? I contend we’re not. And it’s not our fault.

WHAT IS LISTENING?

From the work I’ve done unpacking how our brains make sense of incoming messages, I believe that listening is far more than hearing words and understanding another’s shared thoughts and feelings.

There are several problems with us accurately hearing what someone says, regardless of our intent to show up as empathetic listeners. Listening is actually a brain thing that has little do to with meaning: our brains determine what we hear. And they weren’t designed to be objective. There are two primary reasons:

- Words, considered meaningless puffs of air by neuroscientists, are meant to be semantic transmissions of meaning, yet emerge from our mouths smooshed together in a singular gush with no spaces between them.

- Our brains then decipher individual sounds, individual word breaks, unique definitions, to understand their meaning. No one speaks with spaces between words. Otherwise. It. Would. Sound. Like. This. Hearing impaired people face this problem with new cochlear implants: it takes about a year for them to learn to decipher individual words, where one word ends and the next begins. When others speak, their words enter our ears as meaningless electrochemical sound vibrations – puffs of air without denotation until our brain translates them, paving the way for misunderstanding.

- Due to the way sound vibrations are turned into electrochemical signals in our brains and uniquely translated according to historic neural circuits, our ears hear what we’ve heard before, not necessarily an accurate rendition of what a speaker intends to share.

Just as we perceive color when light receptors in our eyes send messages to our brain to translate the incoming light waves (the world has no color), meaning is a translation of sound vibrations that have traversed a very specific brain pathway after we hear them.

As such, I define listening as

our brain’s progression of making meaning from incoming sound vibrations – an automatic, electrochemical, biological, mechanical, and physiological process during which spoken words, as meaningless puffs of air, eventually get translated into meaning by our existing neural circuitry, leaving us to understand some unknown fraction of what’s been said – and even this is biased by our existing knowledge.

HOW BRAINS LISTEN

I didn’t start off with that definition. Like most people, I had thought that if I gave my undivided attention and listened ‘without judgment’, I’d be able to hear what a Speaker intended. But I was wrong.

When writing my book WHAT? on closing the gap between what’s said and what’s heard, I was quite dismayed to learn that what a Speaker says and what a Listener hears are often two different things.

It’s not for want of trying; Listeners work hard at empathetic listening. But the way our brains are organized make it difficult to hear others without bias.

Seems everything we perceive is translated (and restricted) by the circuits already in our brains. If you’ve ever heard a conversation and had a wholly different takeaway than others in the room, or understood something differently from the intent of the Speaker, it’s because brains have a purely mechanistic and historic approach to translating incoming content.

Here’s a simplified version of what happens when someone speaks:

– the sound of their words enter our ears as mere vibrations (meaningless puffs of air),

– and face dopamine, which distorts the incoming message/sound vibrations according to our beliefs.

– What’s left gets turned into electro-chemical signals (also meaningless) that

– get sent for translation to existing circuits, with

– a ‘close-enough’ match to historic circuits

– that then discard whatever doesn’t match

– causing us to ‘hear’ some unknown fragments of messages

– translated through circuits we already have on file (i.e. We translate incoming words through our historic circuits, making it almost impossible to accurately hear what’s been said)!

It’s mechanical. And it’s all biased by our own history, regardless of what a speaker says or intends. We hear some subjective version of what we already know.

The worst part is that during the process, when our brain discards signals that don’t match our history, it doesn’t tell us! So if you say “ABC” and the closest circuit match in my brain is “ABL” my brain discards D, E, F, G, etc. and fails to tell me what it threw away!

That’s why we believe what we ‘think’ we’ve heard is accurate. Our brain actually tells us that our biased rendition of what it thinks it heard is what was said, regardless of how near or far that interpretation is from the truth.

With the best will in the world, with the best empathetic listening, by being as non-judgmental as we know how to be, as careful to show up with undivided attention, just about everything we hear is naturally biased. [Note: to address this problem, I developed a unique training that first generates new neural circuits before offering new content so the brain will accurately understand, then retain, the new without bias.]

IT’S POSSIBLE TO GET IT ‘RIGHTER’

The problem is our automatic, mechanistic brain. Since we can’t easily change the process itself (I’ve been developing brain change models for decades; it’s possible to add new circuits.), it’s possible to interfere with the process.

I’ve come up with two ways to listen with more accuracy:

- When listening to someone speak, stand up and walk around, or lean far back in a chair. It’s a physiologic fix, offering an Observer/witness viewpoint that goes ‘beyond the brain’ and disconnects from normal brain circuitry. I get permission to do this even while I’m consulting at Board meetings with Fortune 100 companies. When I ask, “Do you mind if I walk around while listening so I can hear more accurately?” I’ve never been told no. They are happy to let me pace, and sometimes even do it themselves once they see me do it. I’m not sure why this works or how. But it does.

- To make sure you take away an accurate message of what’s said say this:

To make sure I understood what you said accurately, I’m going to tell you what I think you said. Can you please tell me what I misunderstood or missed? I don’t mind getting it wrong, but I want to make sure we’re on the same page.

Listening is a fundamental communication tool. It enables us to connect, collaborate, care, and relate with everyone. By going beyond Active Listening, by adding Brain Listening to empathetic listening, we can now make sure what we hear is actually what was intended.

______________________________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen February 23rd, 2026

Posted In: Communication, Listening

I’m a Loyal Customer. Why Do My Vendors Use Voice Agents that Hate Me? by Sharon-Drew Morgen

Dear Vendor:

Dear Vendor:

I assume you want my business and care about keeping me as a loyal customer. I also assume that whatever you do, whoever you hire, is paid for by my contributions to your coffers and you need me to keep your business afloat. Why, then, do you disrespect me? Insult me? Waste my time? Infuriate me?

I’m writing to tell you that your voice bots and virtual receptionists stink. They waste my time keeping me on hold for hours – Best Buy once kept me on hold for 13 hours (!). When the tech called at 3:10 a.m. and asked (in a perky voice, no less) ‘So how are you today!?’ he hung up on me when I replied: ‘Angry. Why have you kept me on hold since yesterday? Do you know it’s the middle of the night here now?’ – transfer me to incorrect departments, keep playing that insipid music that makes me want to vomit, offer me useless choices and otherwise make it impossible for me to get through to you.

WHY ARE YOU USING VIRTUAL RECEPTIONISTS?

I’d really like to know why you’re using these insulting bits of software. Are you trying to save money? I would think the customers you lose would cost you money in the long run. Not to mention you’re thinking short-term and fail to remember you’re in business to serve. Indeed, every product you sell is a promise to serve. You’ve apparently forgotten your promise. And while large companies can weather some lost business, smaller companies can’t…not to mention they’ve lost an opportunity to touch customers and brand themselves as a caring company that serves customers.

Do you not realize that by not touching customers when they call, you’re giving up the ability to serve and generate trust, hear what’s going on, or understand and resolve the repeating complaints that might eventually lead to new sales? I can’t tell you the number of times good receptionists have led me to resolutions I hadn’t known about, or given me new ideas and ways to use your products.

Maybe there are other reasons: you think your phone bots and virtual receptionists offer me better help than a real human? Maybe – and this seems most likely to me, your customer – you just want me to stop calling. When I call and get these infuriating ‘voices’ and inappropriate options, and am left on hold forever, I’m sorry I purchased anything from you. I certainly won’t do so again. And when friends ask for referrals, I share a story of how you wasted my time and suggest they find another supplier.

PLEASE CALL IN TO YOUR OWN COMPANY

I have a great idea. Call in to your own company. You might be surprised to find you’re offered unhelpful choices. Or face long hold times (and then get dropped). Or get sent to the wrong department – if you ever even get through. Make sure you call when you have no meetings planned because you’ll be put on hold for minutes/hours to ensure you waste your time.

Oh – here’s a hint. Don’t bother telling the bot what you want as you’ll be misinterpreted or given bad/inappropriate choices (Regardless of the question or offered choices, just keep repeating REPRESENTATIVE until you’re screaming it.). You might find yourself annoyed that you’ll need to call back again and again to get through to anyone or anything! Even your own reps don’t want to place a call into your receptionist to help me find the right department after I’ve been sent down a rabbit hole and some sympathetic employee tries to help me.

WHAT IS YOUR GOAL?

I wonder if you even want me as a customer. But maybe that’s your plan – to get me so frustrated that I’ll not call again? That you’ll hope my problem will disappear itself? I recently failed to get through to UPS to file a complaint against a driver for deeply unprofessional behavior. As he was leaving his van to make a delivery, I asked him to move it from my marked parking spot so I could park. He refused, kept walking away, called me a Bitch, then gave me The Finger. Does UPS want their drivers doing that? I would think they’d want to either fire this guy or at least offer him further training. Are they happy to have this guy represent them? Or maybe they just don’t care about their employees or brand either?

Here’s a question: What do you expect me to do when I need you for information, or product support? If you cared about me or your brand, I’d speak with a human to make sure my complaint gets through to the right place, or my problem gets solved.

It seems you don’t care. I, for one, won’t buy from you again. I look forward to the old days, when companies cared about me and keeping my business. What a shame we all have to be at the wrong end of this nonsense now. Fix it.

________________________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com, https://sharondrew1.substack.com/, and https://medium.com/@sharondrew_9898/. She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen January 12th, 2026

Posted In: Communication, Listening

What is Buying Facilitation®? What sales problem does it solve?, by Sharon-Drew Morgen

Going from a successful sales professional to an entrepreneur of a start-up tech company, I realized the problem with sales. As an entrepreneur I tried to tried to resolve problems in-house. When impossible, the next step was to figure out if we were willing to go external and actually buy something, figure out if the ‘cost’, the risk, of making a purchase would carry a greater risk than keeping things as they were.

Going from a successful sales professional to an entrepreneur of a start-up tech company, I realized the problem with sales. As an entrepreneur I tried to tried to resolve problems in-house. When impossible, the next step was to figure out if we were willing to go external and actually buy something, figure out if the ‘cost’, the risk, of making a purchase would carry a greater risk than keeping things as they were.

We ended up fumbling around trying to figure this out, but always moving toward congruent change; I didn’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater. And it wasn’t until we figured out how, if, or when to change without major disruption, and until everyone bought in, I never even considered buying anything.

Along the way I tracked my steps and noticed our decision-making process, a change management process with specific stages, each meant to maintain stability, each meant to find solutions and workarounds that would match our goals and norms.

WHO IS A BUYER

I was surprised to discover that regardless of my need, or any available solutions that I could have purchased earlier, I never considered myself a buyer and ignored all sales content.

This process, this change management process I went through, is something everyone does before they become buyers. In other words, the missing piece in sales was the change piece: if sales first sought folks trying to solve a problem in the area my solution would help them with, then facilitated them through the issues they needed to resolve (job descriptions, goals, buy-in, workarounds, and organizational/internal change) before choosing their least disruptive solution, we’d find folks on route to buying and make their process more efficient.

When we attempt to sell our solutions too early, folks haven’t yet determined their full set of needs, don’t have all the stakeholders on board, haven’t yet tried all workarounds, and generally are not ready to buy. The pitching and presenting, waiting and following up, was falling on deaf ears.

I sure could have used help making the process more efficient; if a sales person had helped me understand the issues my decision-making had to include, I would have figured out a lot sooner if I needed to buy something. But unfortunately, this is overlooked by the sales industry because it is NOT purchase-based.

I finally understood the missing piece in the sales model, the cause of the very low close rates: by assuming someone with ‘need’ is a prospect, we ignore the obligatory change management portion that precedes decision making. What if we added a wholly new skill set to first find folks in the process of change, help them address it, and THEN sell once they became buyers?

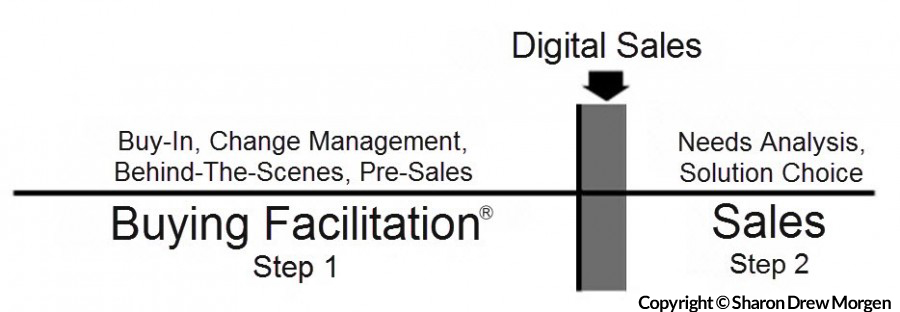

Turns out selling and change facilitation are two distinct endeavors with two distinct skill sets. I decided to develop a front end tool to add to the sales model.

For years I’d been studying NLP and neuroscience to best understand how brains are organized so I could figure out how to make change more efficient. I combined this knowledge with my newfound understanding of what goes on behind-the-scenes on the Buy Side, and developed a generic change facilitation model called Buying Facilitation® as a precursor (and wholly separate model) to sales.

This article introduces you to Buying Facilitation®, a precursor to sales, and a way to facilitate people along their route to buy-in, decision-making, and change. And buying.

DO YOU WANT TO SELL? OR HELP SOMEONE BUY?

BIG IDEA: People don’t want to buy anything, merely solve a problem at the least ‘cost’ (risk) to their system. Until they understand the risk of bringing in something new, they won’t self-identify as ‘buyers’ regardless of their need or the efficacy of your solution.

PROBLEM: People don’t consider they have a need until all workarounds are tried and all stakeholders agree. They won’t heed any selling efforts even if the content offered might solve their problem. By seeking out folks with ‘need’, sellers restrict their audience to the low-hanging fruit – those who have completed their 13 step change management process they must traverse before considering they’ve got a need and become buyers.

SOLUTION: It’s possible to find folks who WILL become buyers on the first call, facilitate them through their change steps with a change/decision model (Buying Facilitation®), and then sell. But because the two endeavors are distinct, trying to incorporate change facilitation with selling causes the same resistance and avoidance sellers currently get.

BIG IDEA: People don’t become buyers until they’ve handled all of their internal stuff, the risk of change is acceptable, and everyone involved agrees they’re ready, willing, and able to bring in something new. With a solution-placement focus, sales and marketing finds only those few who have completed their change process.

PROBLEM: The problem is not in getting our solution sold; it’s in getting our solution bought. Before self-identifying as buyers, people have Pre-Sales, change management work to do that doesn’t involve the content we try to push on them. Our sales and marketing efforts seek to ‘get in’, get read, or determine ‘need’, which restricts the prospect base to people who already know what they need (those who have completed their process).

SOLUTION: Before they become buyers they must assemble the most appropriate people, get consensus, try workarounds, understand the ‘cost’/risk of making a change, and manage the actual change. Current tools only create connections with people already seeing external solutions, but it’s possible to enter earlier with a change toolkit:

- Because of the selling biases in our listening and questioning, sellers extract partial data, from people who don’t have the full fact pattern yet and who haven’t self-identified as buyers;

- promised dates get ignored and we spend huge amounts of time following up people who will never buy because WE think they have a need (and ‘need’ does not a buyer maker);

- we lose an opportunity to connect and prove our competitive worth by entering with a change facilitation purpose first;

- we waste our time pushing content on folks not yet buyers and waiting, hoping they’ll buy, and cause resistance instead of entering earlier to facilitate the change.

Buying Facilitation® uses a very specific tool kit, the Pre-Sales stuff selling doesn’t handle. Once we help with this, we’ve either helped them help themselves, or they realize they cannot solve the problem internally and they become prospects. For these folks, we then sell. These are the folks we would have ended up trying to sell to anyway, but too often we would have been ignored because they hadn’t been ready. Once they’ve reached this point, they are ready buyers and no longer prospects.

BIG IDEA: The flaw in the sales model: designed to place solutions, sales starts selling to anyone they assume has a need, well before people are prospects, before they are ready/able to buy and haven’t gotten the buy-in or understood the ‘cost’ of making a change. This restricts success to those who finally self-identify as buyers – the low-hanging fruit (5%).

PROBLEM: The status quo is preferred and is the basis of decision making. Regardless of a buyer’s real need (which they often don’t understand until very late in the change cycle), or the relevance of a solution; regardless of relationship or pitch/content/price; it is only when they’ve completed their change and all agree they need an external solution that they consider buying anything. This holds true regardless of type or price of solution.

SOLUTION: Buying Facilitation® is a generic, unique brain-based change facilitation model that facilitates people through the obligatory systemic decision-making steps necessary to manage change. Those who end up solving their problem are fine – we’ve served them quickly and there’s no need to follow up. Those who need our solution become prospects and sellers then shift into selling modality to place solutions. It can be used with small personal products, cold calls, help desks, complex sales, and marketing.

Because BF must be unbiased, I developed a new form of listening (Listening for Systems) and a new form of direction-driven/non-biased question (Facilitative Question) to facilitate someone’s journey through the steps of change. Once folks are at the point of becoming prospects and buyers, sellers are already in place and the buy cycle is quick.

But you must remember not to use BF as a selling tool or you’ll end up with the same results you’re getting now. It’s necessary to understand that a buying decision is first a change management problem before a solution choice issue.

Buyers must handle this stuff, with you or without you: you’ve always sat and waited (and called, sent, called, pitched, prayed, waited) while they do this for themselves and the time it takes them is the length of the sales cycle (And no, there is NO indecision!). If you can collaborate with them first as change facilitators, not solution providers, you’ll serve them from the beginning. [Read my book on this: www.dirtylittlesecretsbook.com]

EXAMPLE OF USING BUYING FACILITATION®

Let me lead you through one simple situation from a small business banker I trained at a major US bank. They decided to employ Buying Facilitation® throughout the bank following a successful pilot training:

A. Control group Sales: 100 calls, 10 appointments, 2 closed sales in 11 months.

B. Buying Facilitation®: 100 calls, 37 appointments, 29 closed sales in 3 months.

While these numbers might sound high, remember: interactions proceed differently using Buying Facilitation® because the focus is different: it’s first a call with a change facilitation hat on to (A) find those seeking change, (B) then facilitate them through their entire decision path and (C) then sell to those who become buyers.

Starting by seeking those folks already involved in finding the best route to change, and using ‘change’ rather than ‘need’ as the original focus, there’s different output and the odds of finding and facilitating someone who will become a buyer are high.

Using Buying Facilitation® with a Facilitative Question, my client started like this:

“Hi. My name is John and I’m a small business banker from X bank. This is a sales call. I’m wondering: How are you currently adding new banking resources for those times your current bank can’t give you what you need to keep your business operating optimally?”

Notice he’s not attempting to ‘uncover need’. Here’s the thinking: Given all small businesses have some banking relationship, the only businesses who would want to discuss new banking services were: 1. those who weren’t happy with their current bank, or 2. had bankers who might not be able to provide what they might need.

By helping them figure out where they could add a new resource without disrupting current vendor relationships, my clients vastly expanded the field of possible buyers and instantly eliminated those who would never buy. After all, people have the right to be satisfied with their current vendors!

It proved a winning tactic: 37 were willing to continue the conversation, line up all of the decision factors, figure out who the real stakeholders were, and have everyone meet the seller, just from that opening question (up from 10). During the field visit we helped them get buy-in and consensus to bring in an additional vendor – us. Win/win. Collaboration. True facilitation.

CONCLUSION:

Buying Facilitation® is not sales, not a solution placement tool, not an information gathering tool, and not a persuasion tactic. It’s not content-driven, and sellers don’t try to understand a buyer’s needs because they can’t know their needs until the end of when they’ve become buyers: until they figure out how to manage any change, they are only people trying to solve a problem – not buyers – and they will resist all sales efforts and content. Once all workarounds have been tried, and the ‘cost’ (risk) to the system is understood and found agreeable to all stakeholders, people then self-identify as buyers.

By first facilitating change and decision making before trying to sell, you’ve halved the sales cycle and doubled the folks interested in buying. There’s no manipulation, no persuasion, no influencing. It’s a win/win collaboration, servant leader model that might lead into a sales process: we actually facilitate buyer readiness.

I can’t say this enough: buyers go through this anyway, without us. Let’s use our industry knowledge and be real trusted advisors. Find folks going through change in the area our solution serves, then help them navigate their change before selling. It can be your competitive edge.

And we end up with real prospects who we’ve helped get ready to buy. Not to mention the collaboration, trust, respect, and integrity built into the interaction creates lasting relationships when used throughout the relationship.

The good news is that you can still sell – but only to those who are indeed ready willing and able, rather than waste 90% of your time trying to manipulate, pitch, persuade, push, ‘get through the door’, network, write content, etc. You can help those who CAN buy get their ducks in a row and quickly eliminate those who will never buy because it will become obvious to you both.

I’m not suggesting you don’t sell; I’m merely suggesting you find and facilitate change for those who WILL buy, and set that up by first facilitating prospective buyers down their own buying decision path.

____________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com, https://sharondrew1.substack.com/, and https://medium.com/@sharondrew_9898/. She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen November 24th, 2025

Questioning Questions, by Sharon-Drew Morgen

Decades ago I had an idea that questions could be vehicles to facilitate change in addition to eliciting answers. Convention went against me: the accepted use of questions as information gathering devices is built into our culture. But overlooked is their ability, if used differently, to facilitate congruent change.

Decades ago I had an idea that questions could be vehicles to facilitate change in addition to eliciting answers. Convention went against me: the accepted use of questions as information gathering devices is built into our culture. But overlooked is their ability, if used differently, to facilitate congruent change.

WHAT IS A QUESTION?

Standard questions gather information at the behest of an Asker and as such are biased by their words, goals, and intent. As such, they actually restrict our Communication Partner’s responses:

Need to Know Askers pose questions as per their own ‘need to know’, data collection, or curiosity.

These questions risk overlooking more relevant, accurate, and criteria-based answers that are stored in a Responder’s brain beyond the parameters of the question posed.

Why did you do X? vs How did you decide that X was your best option?

Manipulate agreement/response Questions that direct the Responder to respond in a way that fits the needs and expectations of the Asker.

These questions restrict possibility, cause resistance, create distrust, and encourage lying.

Can you see how doing Y would have been better? vs What would you need to consider to broaden your scope of consideration next time?

Doubt Directive These questions, sometimes called ‘leading questions’ are designed to cause Responders to doubt their own effectiveness, in order to create an opening for the Asker.

These narrow the range of possible responses, often creating some form of resistance or defensive lies; they certainly cause defensiveness and distrust.

Don’t you think you should consider doing X? vs Have you ever thought of alternate ways of achieving X?

Data gathering When worded badly, these questions limit the possible answers and overlook more accurate data.

What were the results of your search for Z? vs How did you choose the range of items to search for, and what results did you get?

Standard questions restrict responses to the Asker’s parameters, regardless of their intent or the influencer’s level of professionalism, care, or knowledge. Potentially important, accurate data – not to mention the real possibility of facilitating change – is left on the table and instead may promote distrust, bad data collection, and delayed success.

Decision Scientists end up gathering incomplete data that creates implementation issues; leaders and coaches push clients toward the change they perceive is needed and often miss the real change needed. The fields of sales and coaching are particularly egregious. The cost of bias and restriction is unimaginable.

WHAT IS AN ANSWER?

Used to elicit or push data, the very formulation of conventional questions restricts answers. If I ask ‘What did you have for breakfast?’ you cannot reply ‘I went to the gym yesterday.’ Every answer is restricted by the biases within the question.

- Because we enter conversations with an agenda, intuition, directive, etc., the answers we receive are partial at best, inaccurate at worst, and potentially cause resistance, sabotage, and disregard.

- There are unknown facts, feelings, historic data, goals, etc. that lie within the Responder’s unconscious that hold real answers and cannot be found using merely the Asker’s curiosity.

- By approaching situations with the natural biases inherent in standard questions, Askers only obtain good data from Responder’s with similar backgrounds and thought processes.

- Because influencers are unaware of how their particular bias restricts an answer, how much they are leaving ‘on the table’, or how their questions have skewered potential, they have no concept if there are different answers possible, and often move forward with bad data.

So why does it matter if we’re biasing our questions? It matters because we don’t get accurate answers; it matters because our questions instill resistance; it matters because we’re missing opportunities to serve and support change.

Imagine if we could reconfigure questions to elicit accurate data for researchers or marcom folks; or enable buyers to take quick action from ads, cold calls or large purchases; or help coaching clients change behaviors congruently, permanently, and quickly; or encourage buy-in during software implementations. I’m suggesting questions can facilitate real change.

WHAT IS CHANGE?

Our brain stores data rather haphazardly in our brain making it difficult sometimes to find the right answer when we need it, especially relevant when we want to make new choices.

Over the last decades, I have mapped the sequence of systemic change and designed a way to use questions as directional devices to pull relevant data in the proper sequence so influencers can lead Responders through their own change process without resistance.

This decision facilitation process enables quicker decisions and buy-in – not to mention truly offer a Servant Leader, win/win communication. Let’s look at how questions can enable change.

All of us are a ‘system’ of subjectivity collected during our lifetime: unique rules, values, habits, history, goals, experience, etc. that operates consensually to create and maintain us. It resides in our unconscious and defines us. Without it, we wouldn’t have criteria for any choices, or actions, or habits whatsoever. Our system is hard wired to keep us who we are.

To learn something new, to do something different or learn a new behavior, to buy something, to take vitamins or get a divorce or use new software or be willing to forgive a friend, change must come from within or it will be resisted.

- People hear each other through their own biases. You ask biased questions, receive biased answers, and hit pay dirt only when your biases match. Everyone else will ignore, resist, misunderstand, mishear, act out, sabotage, forget, ignore, etc.

- Due to their biased and restricting nature, standard questions won’t facilitate another’s change process regardless of the wisdom of your comments.

- Without the Responder being ready, willing, and able to change according to their own criteria, they cannot buy, accept, adopt, or change in any way.

To manage congruent change, and enable the steps to achieve buy-in, I’ve developed Facilitative Questions™ that work comfortably with conventional questions and lead Responders to

- find their own answers hidden within their unconscious,

- retrieve complete, relevant, accurate answers at the right time, in the right order to

- traverse the sequenced steps to congruent, systemic change/excellence, while

- avoiding restriction and resistance and

- include their own values and subjective experience.

It’s possible to help folks make internal changes and find their own brand of excellence.

Facilitative Questions™ (FQs) use a new skill set – listening for systems – that is built upon systems thinking and facilitating folks through their unconscious to discover their own answers.

Using specific words, in a very specific sequence, it’s possible to pose questions that are free of bias, need or manipulation and guide congruent change. And it requires trust that Responders have their own answers.

Facilitative Question™ Not information gathering, pull, or manipulative, FQs are guiding/directional tools, like a GPS system. Using specific words in specific sequences they lead Responders congruently, without any bias, down their unique steps of change to Excellence. How would you know if it were time to reconsider your hairstyle? Or What has stopped you from adding ‘x’ to your current skill set until now?

When used with coaching clients, buyers, negotiation partners, advertisements, or even teenagers, these questions create action within the Responder, causing them to recognize internal incongruences and deficiencies, and be guided through their own options. (Because these questions aren’t natural to us, I’ve designed a tool and program to teach the ‘How’ of formulating them.).

The responses to FQs are quite different from conventional questions. By word sequencing, word choice, and placement they cause the Responder to expand their perspective and recognize a broad swath of possible answers. A well-formed FQ would be one we formulated for Wachovia Bank to open a cold call:

How would you know when it’s time to consider adding new banking partners for those times your current bank can’t give you what you need?

This question shifted the response from 100 prospecting calls from 10 appointments and 2 closes over 11 months to 37 meetings and 29 closes over 3 months. FQs found the right prospects and garnered engagement immediately.

Instead of pulling data, you’re directing the Responder’s unconscious to where their answers are stored. It’s possible Responders will ultimately get to their answers without Facilitative Questions, but using them, it’s possible to help Responders organize their change criteria very quickly accurately. Using Facilitative Questions, we must

- Enter with a blank brain, as a neutral navigator, servant leader, with a goal to facilitate change.

- Trust our Communication Partners have their own answers.

- Stay away from information gathering or data sharing/gathering until they are needed at the end.

- Focus on helping the Other define, recognize, and understand their system so they can discover where it’s broken.

- Put aside ego, intuition, assumptions, and ‘need to know.’ We’ll never understand another’s subjective experience; we can later add our knowledge.

- Listen for systems, not content.

FQs enable congruent, systemic, change. I recognize this is not the conventional use of questions, but we have a choice: we can either facilitate a Responder’s path down their own unique route and travel with them as Change Facilitators – ready with our ideas, solutions, directions as they discover a need we can support – or use conventional, biased questions that limit possibility.

For change to occur, people must go through these change steps anyway; we’re just making it more efficient for them as we connect through our desire to truly Serve. We can assist, or wait to find those who have already completed the journey. They must do it anyway: it might as well be with us.

I welcome opportunities to put Facilitative Questions into the world. Formulating them requires a new skill set that avoids any bias (Listening for Systems, for example). But they add an extra dimension to helping us all serve each other.

____________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com, https://sharondrew1.substack.com/, and https://medium.com/@sharondrew_9898/. She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen November 17th, 2025

Posted In: Communication, Listening

Influencing Congruent, Unbiased Change: serving with integrity, by Sharon-Drew Morgen

As influencers we aim to help Others achieve their own brand of excellence, using their own unique values and standards. Sadly, too many of us – coaches, leaders, sellers, consultants, doctors, parents – try to get Others to accede to our viewpoints and suggestions, believing we have information or solutions that offer ‘better’ choices than the ones they’ve made. We’re telling them, net, net, that we’re smarter, that we think our ideas are better than their own.

It’s not our intent, but due to the way we engage with others, and the way brains work, we inadvertently end up restricting possibility and creating resistance, conflict, antagonism, or disregard, regardless of the efficacy of what we have to offer.

In this article I’ll explain how we end up creating the very resistance we prefer to avoid, and introduce new skills to enable us to truly serve.

WE CONNECT THROUGH OUR OWN SUBJECTIVITY

Regardless of the situation, when we try to effect change using our own viewpoint or beliefs (even if they are valid), our unconscious biases and expectations cause us to inadvertently alienate those who might need us. As a result, we ultimately influence only a percentage of those who need our help – those who already basically agree with us.

I’ll explain, below, how we restrict our interactions and then offer new ways to approach influencing to enable others to find their own best solutions:

Biased listening: We each listen to Others unconsciously, through our brain’s unique and subjective filters (biases, triggers, assumptions, habitual neural pathways, memory channels), regardless of our concerted attempts to accurately hear what’s intended. As a result, what we think we hear is often an inaccurate translation of what was meant and not what the speaker intended.

So our Communication Partner (CP) might say ABC but we actually ‘hear’ ABD (And yes, we often hear something quite different than what was said although it shows up as ‘real’. Read my article on how this happens.) and our brains don’t tell us we’re misunderstanding. Unfortunately, it works both ways and Others also wittingly misconstrue what we’ve said.

I wasn’t fully aware of the extent of this until I researched my book What? Did you really say what I think I heard? on how to hear others without bias. With the best will in the world we end up only accurately hearing, and thereby responding to, some percentage of the message our CPs intend. It’s outside of our conscious awareness. But it’s possible to remedy by listening with a different part of our brain. More on this later.

Fact #1. We hear Others through our subjective biases, assumptions, triggers, habituated neural pathways, and beliefs, causing us to unintentionally misinterpret the message intended, with no knowledge that what we think we’ve heard is mistaken. Obviously this effects both sides of a communication (i.e. Speakers and Listeners).

Subjective expectations: We enter into each conversation with expectations or goals (conscious or unconscious), often missing avenues of further exploration.

Fact #2. Entering conversations with very specific and self-oriented goals or expectations (conscious or unconscious) unwittingly limits the outcome and full range of possibility, and impedes discovery, data gathering, and creativity.

Restricted curiosity: Curiosity is both triggered and restricted by what we already know, i.e. you can’t ask or be curious about something you have no familiarity with to begin with. Using our own goals to pose questions that are often biased, assumptive, leading, etc. we inadvertently reduce outcomes to the biases we entered the conversation with; our subjective associations, experiences, and internal references restrict our ability to recognize accurate fact patterns during data gathering or analysis.

Fact #3: We enable Others’ excellence, and our own needs for accurate data, to the extent we can overcome our own unconscious biases that restrict the range and focus of our curiosity.

Cognitive dissonance: When the content we share – ideas, information, advice, written material – goes against our CPs conscious or unconscious beliefs, we cause resistance regardless of the efficacy of the information. This is why relevant solutions in sales, marketing, coaching, implementations, doctor’s recommendations etc. often fall on deaf ears. We sometimes unwittingly cause the very resistance we seek to avoid when we attempt to place perfectly good data into someone’s idiosyncratic, habituated belief system that runs different to our own.

Fact #4. Information doesn’t teach Others how to change behaviors; behavior change must first be initiated from beliefs, which in turn initiates buy-in.

Systems congruence: Individuals and groups think, behave, and decide from a habitual system of unconscious beliefs and rules, history and experience, that creates and maintains their status quo. We know from Systems Theory that it’s impossible to change only one piece of a system without effecting the whole. When we attempt to offer suggestions that run counter to the Other’s normalized system, we cause Others to risk incongruence and internal disruption. Hence, resistance.

Unfortunately for those of us trying to effect change in Others, it’s important to remember we’re outsiders: as such, we can never fully comprehend the ramifications of adding our new ideas, especially when every group, every person, believes it’s functioning well and their choices are normalized and habituated.

Just because it seems right to us doesn’t mean it’s right for another. Sometimes maintaining the status quo is the right thing to do for reasons we can’t understand; sometimes change can occur only when internal things need to shift in ways we cannot assist with.

Net net, we pose questions biased by our own need to know, offer information and solutions that we want to be adopted/accepted, and focus on reaching a goal we want to reach, all of which cause resistance: without buy-in and a clear route to manage any fallout from the potential change that a new element would cause (regardless of the outsider’s belief that change is necessary), congruent change can’t occur. When the ‘cost’ of the change is more than the ‘cost’ of the status quo, people will maintain the status quo.

Fact #5: Change cannot happen until there appropriate buy-in from all elements that will be touched by the change and there is a defined route to manage any disruption the change would entail.

Due to our standard questions and listening skills and assumptions that our terrific information will help, we end up helping only those few whose brains are set up to change (the low hanging fruit) and failing with those who might need us but aren’t quite ready.

INFORMATION DOESN’T FACILITATE CHANGE

We can, however, shift from having the answers to helping others achieve their own type of excellence (regardless of whether or not it shows up looking like we envisioned). In other words, we can help our CPs change themselves. Indeed, by thinking we have the answers, by driving our own outcomes, we lose the opportunity to serve, enable real change, and make a difference.

Don’t take the need to maintain the status quo lightly. Even patients who sign up for prevention programs have a history of non-compliance: with new food plans, or recommendations of exercise programs that challenge the behaviors they have habituated and normalized (for good or bad), they don’t know how to remain congruent if they were to change. (Note: as long as healthcare professionals continue to push behavior change rather than facilitate belief change first, non-compliance will continue.)

It’s possible to facilitate the journey through our CPs own hierarchy of values and rules, enable buy-in and agreeable change, and avoid resistance – but not by using conventional information gathering/sharing, or listening practices as they all entail bias that will touch only those with the same biases.

To enable expanded and managed choice and to avoid resistance, we must first help Others recognize how to congruently change their own status quo. They may have buy-in issues or resource issues; maybe their hierarchy of values or goals would need to shift, or their rules.

By focusing on facilitating choice/change first we can teach Others to achieve their own congruent change and then tailor our solutions and presentations to fit. Otherwise, our great content will only connect with those folks who already mirror the incoming data and overlook those who might have been able to change if they had known how to do so congruently.

THE SKILLS OF CHANGE

I’ve developed a generic Change Facilitation model, often used in sales (Buying Facilitation®) and coaching, that offers the ability to facilitate change at the core of where our status quo originates – our internal, idiosyncratic, and habituated rules and beliefs.

Developed over 50 years, I’ve coded my own Asperger’s systemizing brain, refitted some of the constructs of NLP, coded the system and sequence of change, and applied some of the research in brain sciences to determine where, if, and how new choices fit.

Using it, Others can consciously self-cue – normally an unconscious process – to enable them to discover their own needs for change in the area I can serve, and in a way that’s congruent with the rules and beliefs that keep their status quo in place.

I’ve trained the model globally over the past 30 years in sales, negotiation, marketing, patient relationships, leadership, coaching, etc. Below I introduce the main skills I’ve developed to enable change and choice – for me, the real kindness and integrity we have to offer.

It’s possible to lead Others through

- an examination of their unconscious beliefs and established systems

- to discover blocks, incongruences, and endemic obstructions

- to examine how, if, why, when they might need to change, and then

- help them set up the steps and means (tactically) to make those changes

- in a way that avoids system’s dysfunction

- with buy-in, consensus, and no resistance.

For those interested in learning more, I’m happy to chat, train, and share. Or feel free to use my thoughts to inspire your own model.

Listening for Systems: from birth we’re taught to carefully listen for content and try to understand the Other’s meaning (exemplified by Active Listening) which, because of our listening filters, often misses the underlying, unspoken Metamessage the speaker intends. By teaching the brain to disassociate and listen broadly rather than specifically, Systems Listening enables hearing the intended message at the root of the message being sent and supersedes all bias on either end. For those interested, read my article on how our listening restricts our worlds.

Facilitative Questions: conventional questions, used to gather data, are biased by the Speaker and interpreted in a biased way by the Responder. The intent of Facilitative Questions (FQ) is to lead listeners through a sequential discovery process through their own (often unconscious) status quo; not information focused and not biased, they are directive, and enable our CPs to discover for themselves the full range of elements they must address to achieve excellence. Here is a simple (out of sequence) example of the differences between conventional questions and FQs. Note how the FQ teaches the Other how to think:

- Conventional Question: Why do you wear your hair like that? This question, meant to extract data for the Speaker’s use, is biased by the Speaker and limits choices within the Responder. Bias/Bias

- Facilitative Question: How would you know if it were time to reconsider your hairstyle? While conventional questions ask/pull biased data, this question sequentially leads the Other through focused scans of unconscious beliefs in the status quo. Formulating them requires Listening for Systems.

Using specific words, in a specific order, to stimulate specific thought categories, FQs lead Others down their steps of congruent change, with no bias. Now we can be part of the process with them much earlier and use our desire to influence change to positive effect. We can actually help Others help themselves.

Steps of change: There is a habituated, idiosyncratic hierarchy of people, rules, values, systems, and history within each status quo. By helping our CPs navigate down their hierarchy they can discover and manage each point necessary to change without disruption or resistance. Until they know how to do this – and note, as outsiders we can NEVER understand this – they can take no action as their habitual functioning (their status quo) is at risk. Offering them our information is the final thing they’ll need when all of the change elements are recognized.

To me, being kind, ethical and true servants, being influencers who can make a difference, means helping Others be all they can be THEIR way, not OUR way. As true servant leaders and change agents we can facilitate real, lasting change and then, when Others know how to change congruently, our important solutions will be heard.

____________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen September 15th, 2025

Posted In: Communication, Listening

Bridging the Gap between What’s Said and What’s Heard, by Sharon-Drew Morgen

I used to assume that what I hear someone say is an accurate interpretation of what they mean. My assumption was wrong; what I think I hear has a good chance of being inaccurate, regardless of how intently I listen. But it’s not my fault.

I used to assume that what I hear someone say is an accurate interpretation of what they mean. My assumption was wrong; what I think I hear has a good chance of being inaccurate, regardless of how intently I listen. But it’s not my fault.

During the years I spent reading, thinking, and researching for my book (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?) on closing the gap between what’s said and what’s heard, I was quite surprised to learn how little of what I think I hear is unbiased, or even accurate. Listening, it turns out, is a brain thing and has little to do with words or intent.

HOW BRAIN’S ‘LISTEN’

When we listen to others, we’re not directly hearing their words or intent but an interpretation of a set of meaningless, automatic neurological activities in our brain that have little-to-no relationship with what’s been said.

What we think we hear is wholly determined by our historic life experiences (education, family, values, Beliefs, mental models) that have been stored in our brain and filter all incoming words:what we hear someone say has been translated by what we’ve heard before, creating biases and assumptions that keep us from translating incoming messages accurately.

Generally speaking, our brain determines what we hear. And it’s not objective. Here’s what happens:

-

- Words are merely puffs of air that emerge from our lungs, formed by our mouth and tongue – meaningless sound vibrations – that enter a Listener’s brain and get made into signals that get sent to ‘similar-enough’, existing brain circuits for translation. In other words, there’s a high probability Listeners can’t accurately understand what’s been said because their brain has translated what’s been said by what they’ve heard before.

- A Listener’s ears

– capture some portion of incoming sound vibrations,

– conducts them through historic filters (Beliefs, mental models, etc.)

– translate the remaining vibrations into signals that get sent to

– match ‘similar-enough’ existing circuits, which

– discard what doesn’t match.

The remainder – with an undetermined relationship to what was intended is – what we think we ‘hear’.

-

- Listeners have no idea what has been discarded in the process of hearing/translating what’s been said. Statistically, we accurately hear no more than 35% of what’s been said.

- Both Speakers and Listeners have no idea how a Listener’s brain has interpreted or biased what been said or how close to accurate it’s been received. We all assume what we think we hear is accurate, although it rarely is.

- We speak in run-on sentences, not individual words, and a Listener’s brain must make sense of the variations in vibrations of each word.

- People speak for approximately 600 milliseconds; Listeners begin formulating their response in 200 milliseconds. Approximately two thirds of what’s been said is not even heard.

What we think we hear is some version of our history of hearing something similar. With people we’re in regular contact with and already have circuits to translate, it can be pretty accurate. With others not so much.

DIAGRAM OF HOW BRAINS ‘LISTEN’

Herein lie the gap between what’s said and what’s heard: we all make inaccurate assumptions of what we think we hear, causing us to respond and choose actions from a restricted or flawed knowledge base. Of course, it’s not done purposefully, but it sure plays havoc with communication and relationships.

I once lost a business partner because he misinterpreted something he thought I said, even though his wife told him he had misheard. His comment: “I heard it with my own ears! Are you both telling me I’m crazy??” and stormed out, never to speak to me again.

Unfortunately, and different from perceived wisdom, brains don’t allow us to ‘actively listen’ to accurately understand what’s been said. Sure, Active Listening allows us to ‘hear’ the words spoken but doesn’t capture the intent, the underlying meaning. And given our neurological hearing processes are automatic, mechanical, and thoughtless, we’re stuck with what we think we hear. Here’s a simplified diagram of the process of listening:

Incoming sound vibrations as electrochemical signals get distorted and deleted through the brain’s filtering and transmission processes, eventually getting translated by ‘similar-enough’ existing neural circuits causing us to hear some rendition of what we’ve heard historically. There’s little chance any of us can understand a Speaker’s intended meaning accurately.

GUIDELINES TO MAXIMIZE UNDERSTANDING IN DIALOGUE

Given how vital listening is to our lives, for those times we want to make sure we understand and get on the same page with a Communication Partner (CP) to reach consensus, here are some guidelines:

Get agreement for a dialogue: Often, Communication Partners have different life experiences and, potentially different goals – many of which might be unconscious. Begin by agreeing to find common ground.

“I’d like to have a dialogue that might lead to us to a path that meets both of our goals. If you agree, do you have thoughts on where you’d like to begin?”

“I wonder if we can find common goals so we might find agreement to work from. I’m happy to share my goals with you; I’d like to hear yours as well.”

Set the frame for common values: At a global level, we all have similar foundational values, hopes and fears – for family, food, shelter, health. Start by ‘chunking up’ to find areas of agreement.

“I’d like to find a way to communicate that might help us find a common values so we can begin determining if we share areas of agreement. Any thoughts on how you’d like to proceed?”

“It seems we’re in opposite mind-sets. How do you recommend we go about finding if there’s any agreement we can start from?”

Get agreement on the topics in the conversation: One step at a time; make sure CPs agree to each item and skip the ones (for now) where there’s no agreement. (Put them in a Parking Lot for your next conversation.) Work with ‘what is’ instead of ‘what should be.’

Enter without bias: Unintentionally our historic, unconscious beliefs restrict our search for commonality. Replace emotions and blame with a new bias for this conversation: the ‘bias’ of collaboration.

“I’m willing to find common ground and would like to put aside my normal reactions for this hour but it will be a challenge since my feelings are so strong. Do you also have strong feelings that also might bias our communication? I wonder if we could share our most cherished beliefs and then discuss how we can move forward without bias.”

Get into Observer: To help overcome unconscious biases and filters, here are a few mind hacks that will supersede automatic brain processing: in your mind’s eye, see yourself on the ceiling looking down on yourself and your CP. I call this the Observer (witness, coach) position. It will provide a different viewpoint for your brain, replacing the emotional, automatic response with a broader, far less biased, view of your interaction. Another way is to walk around during the conversation, or sit way, way back in a chair. Sitting forward keeps you in your biases. (Chapter 6 in What? teaches how to stay in Observer and reduce bias.). From your Observer place, notice elements of the communication of both you and your CP:

-

-

- Notice body language/words: Similar to how your brain filters incoming words, your CP is speaking/listening from their filters and assumptions, which will be exhibited in their body language and eye contact. From Observer notice how their physical stance matches their words, the level of passion, feelings, and emotion. Now look down and notice how you look and sound in relation to your CP. Just notice. Read Carol Goman’s excellent book on the subject.

- Notice triggers: Emphasized words hold beliefs and biases. You may also hear absolutes: Always, Never; lots of You’s may be the vocabulary of blame. Silence, folded arms, a stick-straight torso may show distrust. Just notice where/when it happens for you both. If your CPs words trigger you into your own subjective viewpoints, you’ve gotten out of Observer and must get back onto the ceiling where you have choice. But just in case:

-

“I’m going to try very hard to speak/listen without my historic biases. If you find me getting heated, or feel blame, I apologize as that’s not my intent. If this should happen, please tell me you’re not feeling heard and I’ll do my best to work from a place of compassion and empathy.”

Summarize regularly: Because the odds are bad that you’ll accurately hear what your CP means to convey, summarize what you think you heard after every exchange:

“Sounds to me like you said, “XX”. Is that correct? What would you like me to understand that I didn’t understand or that I misheard?”

“I’ statements: Stay away from ‘You’ if possible. Try to work from the understanding that you’re standing in different shoes and there is no way either of you can see the other’s landscape.

“When I hear you say X it sounds to me like you are telling me that YY. Is that true?”

“When I hear you mention Y, I feel like Z and it makes me want to get up from the table as I feel you really aren’t willing to hear me. How can we handle this so we can move forward together?”

Get buy-in each step of the way: keep checking in, even if it seems obvious that you’re on the same page. It’s really easy to mistranslate what’s been said when the listening filters are different.

“Seems to me like we’re on the same page here. I think we’re both saying X. Is that true? What am I missing?”

“What should I add to my thinking that I’m avoiding or not understanding the same way you are? Is there a way you want me to experience what it looks like from your shoes that I don’t currently know how to experience? Can you help me understand?”

Check your gut: Notice when/if your stomach gets tight, or your throat hurts. These are sure signs that your beliefs are being stepped on and you’re out of Observer. Get back up to the ceiling and then tell your CP:

“I’m experiencing some annoyance/anger/fear/blame. That means something we’re discussing is going against one of my beliefs or values. Can we stop a moment and check in with each other so we don’t go off the rails?”

Get agreement on action items: Simple steps for forward actions will become obvious; make sure you both work on action items together.

Get a time on the calendar for the next meeting: Make sure you discuss who else needs to be brought into the conversation, end up with goals you can all agree on and walk away with an accurate understanding of what’s been said and what’s expected.

COMPASSION, EMPATHY, AND RESPECT

Until or unless we all hold the belief that none of us matter if some of us don’t; until or unless we’re all willing to take the responsibility for each (inadvertent)act of harm; until or unless we’re each willing to put aside our very real grievances to seek a higher good, we’ll never heal.

It’s not easy. But by learning how to hear each other with compassion and empathy, by closing the gap between what’s said and what’s heard, our conversations can begin. We must be willing to start sharing our Truth and our hearts and find a way to join with another’s Truth and heart. By hearing each other accurately, it’s the best start we can make.

______________________

Sharon-Drew Morgen is a breakthrough innovator and original thinker, having developed new paradigms in sales (inventor Buying Facilitation®, listening/communication (What? Did you really say what I think I heard?), change management (The How of Change™), coaching, and leadership. She is the author of several books, including her new book HOW? Generating new neural circuits for learning, behavior change and decision making, the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell). Sharon-Drew coaches and consults with companies seeking out of the box remedies for congruent, servant-leader-based change in leadership, healthcare, and sales. Her award-winning blog carries original articles with new thinking, weekly. www.sharon-drew.com She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

Sharon Drew Morgen August 25th, 2025

Posted In: Listening

Sales as a Spiritual Practice

With untold millions of sales professionals in the world, sellers play a role in any economy. As the intermediary between clients and providers, sales can be a spiritual practice, with sellers becoming true facilitators and Servant Leaders (and close more sales).

The current sales model, directed at placing solutions and seeking folks with ‘need’, closes 5% – only those ready to buy at point of contact. Sadly, this ignores the possibility of facilitating and serving the 80% of folks on route to becoming buyers and not yet ready.

Until people have tried, and failed, to fix their problem themselves, understood and managed the risk and disruption that a new solution might cause their environment, they aren’t buyers. It’s only when they:

- know how to manage the risk of bringing in something new,

- can’t fix the problem themselves,

- get buy-in from whomever will touch the final solution,

- understand that the cost of bringing in something new is lower than the cost of maintaining the status quo,

will they self-identify as buyers and be ready to buy.

Indeed: buying is a risk/change management problem before it’s a solution choice issue, regardless of the need or the efficacy of the solution. All potential buyers must go through this process anyway – and the sales model doesn’t help.

WHY PEOPLE BUY

People don’t start off wanting to buy anything; they merely seek to resolve a problem at the least ‘cost’ (risk) to their system. Even if folks eventually need a seller’s solution, until they understand how to manage the change a new solution would generate, they won’t heed our outreach, regardless of their need or the efficacy of the solution. As a result, sellers with worthwhile solutions end up wasting a helluva lot of time being ignored and rejected.

Selling doesn’t cause buying. Sales focuses on only the final steps of a buying decision and overlooks the high percentage of would-be prospects who WILL become buyers once they’ve addressed their possible risk issues. After all, until they’ve recognized that the risk of the new is less than the risk of staying the same they won’t do anything different.

It’s not the solution being sold that’s the problem, it’s the process of pushing solutions before first helping those who will become buyers facilitate their necessary change process. Instead of a transactional process, sales can be an expansive, collaborative experience between seller and buyer.

As a result, sellers end up seeking and closing only those ready to buy at the point of contact – unwittingly ignoring others who aren’t ready yet, may need our solutions, and just need to get their ducks in a row before they’re prepared to make a decision.

Imagine having a product-needs discussion about moving an iceberg and discussing only the tip. That’s sales; it doesn’t facilitate the entire range of hidden, unique change issues buyers must consider – having nothing to do with solutions – before they could buy anything. Failure is built in.

But when sellers redirect their focus from seeking folks with ‘need’ to those considering change and lead them through their change management process before selling, they can facilitate them through the issues they must resolve (politics, relationships, resource, budget, time), help them assemble the right stakeholders from the start, and help them figure out how to address the disruption of bringing in a new solution. Then sellers become true servant leaders, inspire trust, and close more sales.

WHY SALES FAILS

Seller’s restricted focus on placing solutions, and listening for needs (which cannot be fully known until the change management process is complete) all but insures a one-sided communication based on the needs of the seller:

- Prospecting/cold calling – sellers pose biased questions as an excuse to offer solution details omitting those who will buy – real buyers! – once they’re ready. Wholly seller-centric.

- Content marketing – driven by the seller to push the ‘right’ data but really only a push into the unknown and a hope for action. Wholly seller-centric.

- Deals, cold-call pushes, negotiation, objection-handling, closing techniques, getting to ‘the’ decision maker, price-reductions – all assuming buyers would buy if they understood their need/the solution/their problem, all overlooking the real connection and service capability of addressing the person’s most pressing change issues. Wholly seller-centric.

To become a spiritual practice, sellers must use their expertise to become true facilitators that become necessary components in all buying decisions. Indeed, the job of ‘sales’ as merely a solution-placement vehicle is short-sighted.

- Buyers can find products online. They don’t need sellers to understand the features and benefits.

- Choosing a solution isn’t the problem. It’s the time it takes to manage the risk. – it’s the buyer’s behind-the-scenes timing, buy-in from those who will touch the solution, and change management process that gums up the works.

- The lion’s share of the buying decision (9 out of a 13 step decision path) involves buyers traversing internal change with no thoughts of buying. They don’t even self-identify as buyers until they understand their risk of change.

Since the 1980s, I’ve been an author, seller, trainer, consultant, and sales coach of the Buying Facilitation® model. And though I’ve trained 100,000 sales professionals, and wrote the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity, sales continues to be solution-placement driven. By ignoring a large population of potential buyers who merely aren’t ready, sales unwittingly ignores the real problem: it’s in the buying, not the selling.

SERVE PROSPECTS, CLOSE MORE SALES

It’s possible to truly serve clients AND close more sales.

Aspiring to a win-win

Win-win means both sides get what they need. Sellers believe that placing product that resolves a problem offers an automatic win-win. But that’s not wholly accurate. Buying isn’t as simple as choosing a solution. The very last thing people want is to buy anything, regardless of their apparent need.

As outsiders sellers can’t know the tangles of people and policies that hold a problem/need in place. The time it takes them to design a congruent solution that includes buy-in and change management is the length of their sales cycle. Buyers need to do this anyway; it’s the length of the sales cycle.

If sellers begin by finding those on route to buying and help them efficiently traverse their internal struggles, sellers can help them get to the ‘need/purchase’ decision more quickly and be part of the solution – win-win. No more chasing those who will never close; no more turning off those who will eventually seek our solution; no more gathering incomplete data from one person with partial answers.

Sellers can find and enable those who can/should buy to buy in half the time and sell more product – and very quickly know the difference between them and those who can never buy.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts

There are several pieces to the puzzle here.

- The buyer and the environment the prospect lives in, including people, policies, job titles, egos, relationships, politics, layers of management, rules, etc. that no one on the outside will ever understand. It’s never as simple as just changing out the problem for a new product; they will buy only when they’re certain they can’t fix their own problem.

- Resolving the problem needs full internal buy-in before being willing to change (i.e. buy) regardless of the efficacy of the fix. A purchase is not necessarily their best solution even if it looks like a fit to a seller.

- The ability of the buyer to manage the disruption that a new purchase would incur on the system, people, and policies. A fix, or purchase, might be worse than the problem.

- The seller and the seller’s product may/may not fit in the buyer’s environment due to idiosyncratic, political, or rules-based issues, regardless of the need.

- The purchase and implementation and follow up that includes buy-in from all who will experience a potentially disruptive change if a new solution enters and shifts their job routines.

There is no right answer

Sellers often believe that buyers are idiots for not making speedy decisions, or for not buying an ‘obvious’ solution. But sales offers no skills to enter earlier with a different skill set to facilitate change or manage risk.

Once buyers figure out their congruent route to change, they won’t have objections, will close themselves, and there’s no competition: sellers facilitate change management first and then sell once everything is in place. No call backs and follow up and ignored calls. And trust is immediate: a seller becomes a necessary partner to the buying decision process.

No one has anyone else’s answer

By adding Buying Facilitation®, collaborative decisions get made that will serve everyone.

Let’s change the focus: instead relegating sales to merely a product/solution placement endeavor, let’s add the job of facilitation to first find people en route to becoming buyers, lead them through to their internal change process first, and then using the sales model when they’ve become buyers.

We can help people self-identify as buyers quickly, with fewer tire-kickers, better differentiation, no competition, and sales close in half the time.

BUYING FACILITATION®

As a seller and an entrepreneur (I founded a tech company in London, Hamburg, and Stuttgart in 1983), I realized that sales ignored the buying decision problem and developed Buying Facilitation® to add to sales as a Pre-Sales tool.

Buyers get to their answers eventually; the time this takes is the length of the sales cycle, and selling doesn’t cause buying. Once I developed this model for my sellers to use, we made their process far more efficient with an 8x increase in sales – a number consistently reproduced against control groups with my global training clients over the following decades.

Buying Facilitation® adds a new capability and level of expertise and becomes a part of the decision process from the first call. Make money and make nice.

Sellers no longer need to lose prospects because they’re not ready, or cognizant of their need. They can become intermediaries between their clients and their companies; use their positions to efficiently help buyers manage internal change congruently, without manipulation; use their time to serve those who WILL buy – and know this on the first contact – and stop wasting time on those who will never buy. It’s time for sellers to use their knowledge and care to serve buyers and their companies in a win-win. Let’s make sales a spiritual practice.