To Change Behaviors, First Change Beliefs: an essay for change agents

Why do people prefer behaviors that obviously lead to less-than-stellar results, especially when our sage advice, rational evidence, well-considered recommendations, and expert knowledge can offer them more successful choices?

Why do people prefer behaviors that obviously lead to less-than-stellar results, especially when our sage advice, rational evidence, well-considered recommendations, and expert knowledge can offer them more successful choices?Whether we’re parents of kids who sometimes need guidance, sellers with great pitches to offer folks who need our solution, coaches helping a client make changes, or doctors offering lifesaving wisdom, we too often sit by helplessly while folks who need our important data ignore us; our brilliant direction, ideas, and advice fall on deaf ears and we fail over and over again to get through to them.

It’s actually our own fault. We’re entering the wrong way, at the wrong time, with the wrong vehicles. Advice, thoughts, recommendations, persuasions – I’ll refer to external data as ‘Information’ – is the very last thing needed. Our communication partners have no idea how to apply it, how to hear it, or what it means to them. To make matters worse our attempts to facilitate change from our own biases and professional beliefs potentially cause resistance and non-compliance where we seek to promote excellence. But let’s start at the beginning.

HOW DO BEHAVIORS CHANGE?

Permanent, congruent change is rarely initiated through the route of changing deficient behaviors. Behaviors are merely the expression of the underlying structure that created and normalized them over time; they can only change once the underlying structure that created and maintains them change in a way that maintains Systems Congruence. It’s a systems problem, as you’ll see. Indeed, actual behavior change is the final element in the change equation.

To help think about this, let’s parallel behaviors with the functionality – the ‘doing’ – of a software app. The functionality of any app is a result of the internal coding; the programming uses lines of code to spell out the specific rules that define and enable specific functionality. To get a function to behave differently – to ‘do’ something different – the underlying programming must change its coding. It cannot change otherwise. Even programs such as Alexa can only behave within the limits of their programming. (And yes, I wish Alexa could wash my windows.)

It’s the same with human behaviors. Behaviors are the ‘function’, the output, the expression, of our mostly unconscious system of beliefs, history, internal rules, culture, goals, etc. – the lines of code – that define our Identity. All of our behaviors have been ‘coded’ by the system to express who we are, just like the function of an app expresses the internal coding. So what we do, how we behave, the choices we make, are defined, regulated, and governed by our system to demonstrate that idiosyncratic set of elements – our personalities, our politics, our job choices, our ethical standards. It’s our Identity. We’re all ‘doing’ who we ‘are’, even when incongruent. Behaviors are how we show up in the world. And it’s impossible to change the functionality via the function.

WHAT IS A MALFUNCTION?

Any problems in our behaviors – our functionality – must be changed by the system that created/maintains them – the programming. When we believe there to be a malfunction in another’s functionality and a behavior change might be optimal, it can’t be fixed by trying to change the place where it’s broken (Hello, Einstein.). Trying to change someone’s behavior, regardless of the need or efficacy of the solution, is a waste of time and in some instances might cause trust issues.

For those of us who influence Others – sales folks, managers, doctors, coaches, consultants – we’ve got to redefine our jobs. Our job as influencers isn’t to push the change we think is needed, but to enable Others to find their own route to their own idiosyncratic, internal congruent change and change their own internal coding.

For that to happen, the internal coding – the entire set of rules that created the current programming malfunction and set of suboptimal behaviors – must shift to reorganize, reprogram itself around a new set of rules that will create a new set of behaviors to match. The problem is that much of this is unconscious and hidden (like in an app), certainly too unique for an Outsider to fully comprehend.

Therein lies the rub: while we may notice (and potentially bias the explanation of) another’s behavioral glitches, it’s not possible to see or understand the underlying coding that caused them or the systemic change issues that would have to be addressed for them to change their programming. I cannot say this enough: It’s not possible to change another’s behavior from the outside; an internal coding change is required from within the person’s system to design different rules that would carry a different expression. We can’t change behaviors: behaviors will change themselves once the program has changed.

How, then, can we, as outsiders, empower Others to make their own changes? Indeed, it’s a both a systems problem and a spiritual one. We can never change another person, but we can serve them in a way to enable them to create congruent change for themselves, using their own brand of Excellence.

OUR INFORMATION CANNOT CAUSE CHANGE

So now we know that Others cannot change their behaviors merely because we (or even they) merely think they should (i.e. the problem with diets, smoking cessation, etc). How, then, can we reconcile the approach we’ve used to effect change? Until now, we’ve used information as our major tool. We offer what seems the most relevant data (a biased process) using our own personal, intuitive approach to influence (a biased process) where we believe the Other needs to be (again, biased by our own beliefs) and wonder why we get push back or noncompliance.

Somehow we believe that if we offer the right data, at the right time, in the right way, it will encourage action. We’ve developed entire professions based on outside ‘experts’ spouting ‘important’ ‘relevant’ ‘rational’ ‘necessary’ data, assuming these brilliant words and rational, sometimes scientific, arguments, carry ‘the answers’. But the information we offer pushes against the status quo, telling the status quo that it’s ‘wrong’, and

- causes resistance and a tightened grip on the behaviors that continue to express the coded, accepted, and maintained, functionality (even when it’s problematic),

- threatens habitual behaviors that have functioned ‘well enough’,

- leaves a breach in functionality,

- offers no new programming/coding to replace the beliefs, rules, etc. that capture the current ‘code’,

- cannot shift the unconscious rules that caused the current functionality.

The information we offer cannot even be understood, heard, or fully utilized used by those we’re intending it for, regardless of our intent or the efficacy of our solution, until the underlying rules, beliefs – status quo – are ready, willing, able to change congruently and be assured there will be no systems failure as a result of the change (Systems Congruence). This is why people don’t take their meds, or buy a solution they might need, or sabotage an important implementation. We’re asking them to do stuff that may (unconsciously) run counter to their systemic configuration, and not providing a route through to their systemic change, hoping that they’ll behave according to our vision of what their change should look like, rather than their own.

As outside influencers, we must facilitate Others to find their own Excellence by changing their own system; we must stop trying to change, influence, persuade, sway, manipulate, etc. Others using our own biased beliefs to inspire them. [Personal Note: My biggest gripe with sales, coaching, training, management, leadership, etc. is that there is a baseline belief that they have the ‘right’ information that the Other needs in order to be Excellent. I reject that; we can only understand what Others are telling us through our own biases. Not to mention trying to ‘fix’ another is disrespectful and goes against every spiritual law.]. Indeed, as we see by our failures and the low adoption rate, it’s not even possible.

There are two reasons for this: because we filter everything we hear from Others as per our own programming and listening filters (biases, habits, assumptions, triggers, neural pathways, etc.), we can’t be certain that what we think is needed is actually what’s needed; Others can’t understand what we’re trying to share due to their own filters and programming.

Indeed, when we share information before the system has already shifted its internal rules and programming to include a possibility of congruent, alternate choices, it will be resisted and rejected (and possibly shut down the system) as the system has no choice but to defend itself from possible disruption.

THE STEPS OF CHANGE

I have Asperger’s, and part of my life’s journey has included making the personal changes necessary to fit in, to have relationships, to work in conventional business environments without being too inappropriate. To this end, and in the absence of the type of information available now (i.e. neuroscience, brain studies, etc.) I’ve spent decades coding how to change my own brain, and then scaling the process for others to learn. [Personal note: After working with one inside sales group in Bethlehem Steel for two years, I was introduced to the head of another group I’d be working with. Behind me, I heard the new director say to my client: ‘Is she ALWAYS like this??’ to which Dan replied, ‘Yes. And you’ll learn to love her.’ So apparently, I am still a bit odd, although it seems normal to me.]

The steps of change I’ve coded are systemic (i.e. points of activity, not content-based) and are involved in any human change (see below). Each stage is unique, and designate the touchpoints into the unconscious that enables the brain to discern for itself where, if, or how to reexamine itself for congruency. I know there is no referent for it in conventional thinking. But I’ve trained this material, with simultaneous control groups, in global corporations, to 100,000 people and know it’s viable, scalable, highly successful, and useful in any industry or conversations that encourage change. This includes sales, coaching, management, marketing, health care, family relationships and communication, negotiation, leadership.

I start with understanding that I have no answers for Another, as I’ll never live the life they’ve lived; if it’s a group or company, I’ll never understand how the internal system has been historically designed to design the output that shows up. But I trust that when systems recognize an incongruence, they will change (A ‘rule’ of systems is that they prefer to be congruent.). My job as a change agent is to teach a system how to recognize an incongruence and use its own rules to fix itself. I use this thinking to facilitate buyers through their Pre-Sales change management issues, enable coaching clients to determine how to recognize their own systemic elements to change, help leaders obtain buy-in and Systems Congruence (and notice all potential fallout points) before a project.

There are 13 steps to systemic change, all of which must be traversed before a systems is willing/able to change. Here are the 3 main categories of the steps [Personal Note: I explain each step and the navigation of change in Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell]:

1. Where am I; what’s missing. The system must recognize all – all – elements that have created and maintain its status quo so it can determine if/where there are incongruences. Until or unless ALL of the elements are included, there’s no ability to recognize where any incongruence might lie: when you’re standing in front of a tree, you can clearly see the leaves and veins on any particular leaf. But you cannot see the fire 2 acres away. Until the system has an ability to go into Witness/Observer, it cannot assemble the full set of relevant elements, and therefore cannot see the full fact pattern and will continue doing what it’s always done.

RULE: for any change to occur, the system must have a view of the entire landscape of ‘givens’ involved without restriction. To do that it’s necessary for both Influencer and Other to be in Observer – with no biased attachment.

2. How can I fix this myself? Systems are complete as they are and don’t judge ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. They show up every day and re-create yesterday as a way to maintain Systems Congruence. When there is a recognition of an incongruence (as per #1), all systems attempt to fix the problem themselves rather than allow anything new (and by definition incongruent) into the system.

RULE: it is only when a system recognizes it cannot fix an incongruence by itself is it willing to accept the possibility of bringing in an external, foreign solution (i.e. information, advice, new product). First it MUST first figure out how to maintain Systems Congruence and get buy-in from the elements that will be effected.

3. How can I change congruently without disrupting the functionality of the system? What elements need to shift, how do they need to shift, and what needs to happen so the system ends up congruent after change? Using the programming metaphor, the system must understand how it will still end up as a CRM app, or a toaster, if some of the coding needs to change.

RULE: until all elements that will be effected buy-in to any proposed change, the system will continue its current behaviors regardless of its problematic output (After all, that’s the way it ‘is’.)

Once you understand the steps to congruent change, you realize the inefficiency of trying to create change through information sharing, or the impossibility of trying to shift behaviors from outside.

CHANGE FACILITATION

The model I developed is a Change Facilitation model (registered decades ago as Buying Facilitation®) that teaches Others to traverse the steps of change so each element is assembled and handled sequentially. While I often teach it (and write books about it) in the field of sales to enable sellers to facilitate buyers through their ‘Pre-Sales’ steps to change management, the model is generic.

It includes a few unique skill sets that enable Others to recognize unconscious incongruence, and change themselves congruently using their own internal system. They’re different from what’s conventionally used, and need training to learn as we’ve not been taught to think this way. Indeed, there is no referent for these in conventional thinking, and like anything that threatens the status quo, often misunderstood or rejected. I can teach these skills through self-learning (Guided Study for complete knowledge, or Learning Accelerators for spot skills), group or personal training or coaching. I offer a caveat to those who try to add my ideas to their current thinking: when you add any of my ideas on top of what you’re already doing, you’ll end up with more bias, continuing the failure you’re experiencing. Here’s a description of the skills, with links to articles that offer a further explanation:

1. Systems listening: Without listening for systems, and using the conventional listened we’re trained from birth, we can only notice/listen for the content we want to hear. But everything we hear, leading to the assumptions we make, is biased. Indeed, we all speak and listen through biased filters. Always. (When I wrote/researched my book What? Did you really say what I think I heard? I was horrified to realize how little it’s possible to truly hear what others mean due to the way our filters cause us protect our status quo for stability.) Without getting into Witness/Observer to listen for systems, our listening is restricted to our own beliefs and we cannot expand the scope of what’s being said outside of our own systemic belief systems.

2. Facilitative Questions: This is not a conventional question. It does NOT gather data, or use the biases of the questioner, but point the Other’s conscious mind to the specific memory channels that direct the Other to where the most appropriate answers are stored. So:

How would you know if it were time to reconsider your hairstyle? Uses ‘how’ ‘know’ ‘if’ ‘time’ ‘reconsider’ as routes to specific memory channels, create a step back – a Witness overview – that enables the full view of givens and an unbiased scrutiny of the system.

These questions use specific words, in a specific order, to cause the Other to traverse down the steps of unconscious change by putting them into Observer and enabling them to peruse the entire landscape of givens in the order their brains won’t feel pushed or manipulated. It takes my clients about a month to learn how to formulate these. And to do so, it’s necessary to listen differently, since bias is an enemy.

3. Presumptive Summaries: These are one route to enable Others to get into the Witness/Observer stance. Used carefully, they bring our communication partners outside of their own unconscious thinking.

Patient: I just stopped taking my meds.

Doctor (Using a Presumptive Summary): Sounds like you’ve decided that either you’re no longer sick and are now healthy, or you’ve chosen to maintain your status quo regardless of the outcome.

Different from “Why do you do that?” or “But you’ll get sick again.” comments that enlist resistance or defensiveness, Presumptive Summaries just offer a mirror and allow the Other to make conscious what might have been unconscious. These must be used with knowledge and care or they can become manipulative, and will break trust.

4. Traversing the route to change: I pose Facilitative Questions down the steps of change (iteratively, sequentially) so the brain can recognize how, what, when, why, if to change, have no resistance, notice incongruences without defense, and get the buy-in and route design, for congruent change.

All of these require the influencer to have a goal of facilitating their own congruent, systemic change without the biases we usually impart (and get resistance).

I know that most change agents truly want to enable congruent, permanent change. But it’s a crap shoot if you’re using your ‘intuition’ (biased judgment), line of questions (restricting the range of possible answers), biased listening, or ‘professional’ knowledge (biased by the scope of the academic culture) to the change you believe is necessary. It’s truly possible to help Others find their own route to Excellence. It just can’t happen any other way.

If you’re interested in learning how to facilitate congruent change in others – for sales, coaching, therapy, leadership, healthcare, etc. – please let me know. I’d love to help you learn. As I face the aging process, I’m quite keen on handing over this material, developing new apps that use it, designing training, or coaching. Please contact me at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.

If you wish further reading: Practical Decision Making; Questioning Questions; Trust – what is it an how to initiate it; Resistance to Guidance; Influencers vs Facilitators.

__________

Sharon Drew Morgen is a Change Facilitator, specializing in buy-in and change management. She is well known for her original thinking in sales (Buying Facilitation®) and listening (www.didihearyou.com). She currently designs scripts, programs, and materials, and coaches teams, for several industries to enable true buy-in and collaboration. Sharon Drew is the author of 9 books, including the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity, and the Amazon bestsellers Dirty Little Secrets – why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell, and What? Did you really say what I think I heard? Sharon Drew has worked with dozens of global corporations as a consultant, trainer, coach, and speaker. She can be reached at sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.

Sharon Drew Morgen June 10th, 2019

Posted In: Change Management, Communication, Listening

Asperger’s put to work: an essay on coding choice and decision making

I wasn’t diagnosed with Nonverbal Learning Disorder – NLD, similar to Asperger’s – until I was 61. For most of my life it’s felt like I live in a quarantined room with glass walls, watching people live seemingly normal lives on the other side, but unable to touch them. But my world, although far less social, is rich; every day I awake filled with curiosity and visions of possibility, with ideas to write about and share so others can use; every day my heart aches with the need to use my abilities to make a difference and help everyone have the tools to be all they can be.

I wasn’t diagnosed with Nonverbal Learning Disorder – NLD, similar to Asperger’s – until I was 61. For most of my life it’s felt like I live in a quarantined room with glass walls, watching people live seemingly normal lives on the other side, but unable to touch them. But my world, although far less social, is rich; every day I awake filled with curiosity and visions of possibility, with ideas to write about and share so others can use; every day my heart aches with the need to use my abilities to make a difference and help everyone have the tools to be all they can be.

Since I was a kid I’ve had to navigate social situations that render me confused and obnoxious: expected social norms are often incomprehensible to me (I’ll never understand why strangers ask “How are you?” when it’s such a personal question.). My listening skills, apparently, aren’t conventional either: I hear, and respond to, the meaning behind words rather than those spoken. [Note: Like many Aspies, I hear whole circles/systems when spoken to, and often respond to the metamessage intended instead of the words spoken. It gets to the heart of any communication quickly. Clients love it, friends tolerate it, strangers mock it or call me ‘rude’.]. The world’s just different for me.

As a kid my grades suffered until someone figured out I should be given essays instead of multiple choice tests (Then I got A’s). I couldn’t make friends (no sleepovers, or parties, either in high school or college!) even though I was a cheerleader, the school pianist, and editor of the school paper. And everyone, including my confounded parents, tried to make me ‘normal’ when I did something ‘odd’ or ‘bad’. [In those days there was no diagnosis]. Why couldn’t they see/hear/feel me and appreciate my ideas and heart? Why didn’t anyone just accept and encourage me? I knew I was smart and kind. It confused me that others couldn’t see me because I was different.

I prayed to be normal, to understand what responding ‘appropriately’ meant. I longed to join the world, to fit in when I wanted to, but didn’t want to lose my authenticity or ideas. I was determined to figure out how Others made choices, how I made mine, and note the differences. I remember telling myself that since I was in trouble all the time anyway I might as well be in trouble for doing what I thought was right, so long as I knew the difference. This formed the foundation of my life’s work: figuring out how people could make new, congruent choices. In retrospect, I cannot imagine what made me think I could accomplish this. But I did. I just did it my way.

HOW DO WE CHOOSE WHAT WE CHOOSE?

Starting at age 11 I stole away to a large, flat rock in a nearby reservoir to think. From 1957 – 1963 I filled notebooks with ideas, drawings and doodles, and fantasized possibilities: how do people choose? What exactly, is choice, and how do people know when to choose to do something different? Do one thing over another? These questions have filled my entire life. [No Google, no computers, no neuroscience or behavioral science or Daniel Kahneman. Just me, a rock, some paper and pen, and intense curiosity.] It became my ‘topic’: What caused people to think, and act, differently from each other, sometimes with the same set of ‘givens’? Could people be taught when, if, or how to make different choices? Could I change? Could anyone?

I also wrote down conversations – with my parents, and those I overheard – noting similarities and differences in words, responses, and intent; I noted when Others’ behaviors and dialogues were confusing, and when I got in trouble for not making the right choices. I wrote down my own internal dialogue when I was apparently out of step, and noted the social situation when I noticed others said something different than they meant.

It was obvious that people reacted differently to the same stimulus. Seemed everyone’s subjective experience (I call it a system of unique rules, norms, beliefs, experience, history etc.) creates the unconscious biases that cause their habitual choices.

1. Everyone’s choices come from their unique, historic, subjective internal realities (their ‘system’) and are largely unconscious.

I collected data in my jobs: From 1975 – 1979 I ran pre-discharge groups and family therapy in an in-patient state psychiatric center giving me an invaluable opportunity to learn about group communication, hidden agendas and veiled meanings, and the vulnerability of maintaining the status quo. 1979-1983 I was a stockbroker on Wall Street. From 1983-1989 I founded a tech company in London, Hamburg, and Stuttgart and had the opportunity to negotiate and have clients/staff from different countries and cultures. I’ve run Buying Facilitation® training programs in 5 of the 7 continents. I founded a Not-For-Profit around Europe that helped kids with my son’s disease get the resources to lead functional lives. Then, and to this day, I have mapped communication, choice, and belief-based decision making.

HOW WE MAINTAIN OUR STATUS QUO

One of my persistent bewilderments was why people behaved in destructive ways even when they had relevant data suggesting they try something else. As I got better at mapping the elements behind my own decision making process and matching it to what I noticed in Others, I realized the complexity of the problem: there’s a broader set of considerations involved than just ‘fixing’ it, or weighting choices. Seems there are iterative, sequential steps that must occur internally before any system is ready for change (Read Dirty Little Secrets for a complete discussion.) including:

2. A. assembling the full, unique data set that comprises the status quo. Includes rules, values, goals, relationships/people, history, events, etc.;

B. a recognition of anything and everything missing in the status quo that might lead to a problem or a lack [omitting anything causes incomplete, possibly inaccurate data; attempting to push anything in prematurely causes resistance to avoid system destabilization.].

Given the subjectivity and sophistication involved in this process, any change we each to through obviously must be initiated, defined, and accepted from within our indvidual systems; change being pushed from outside gets resisted because it potentially offends the system. Our human systems are sacrosanct.

3. Change must come from within the elements of the system that created the problem to ensure the status quo is maintained.

4. Any potential change must be agreed upon (i.e. buy-in) by the system of rules, experiences, history, people, values (etc.), that hold the initiating problem in place.

Here is the question that has ruled my thinking for decades: How could I, or anyone (given we’re each operating from unconscious subjective biases), facilitate change in Others if their change factors are unconscious and fight to maintain the status quo?

PUSHING CHANGE VS FACILITATING CHANGE

In the mid-1980s I discovered NeuroLinguistic Programming (NLP – the study of the structure of subjective experience) and studied for three years (Practitioner, Master Practitioner, and a unique Beyond/Integration year) because I found their unwrapping of human systems cogent and important. While it’s not scientifically accepted, NLP is quite important as a way to unpack how/why we do what we do and is the most important communication tool of the twentieth century. I loved the depth of the discovery process through their codified systems of human criteria. Unfortunately, like other influencer models (sales, leadership, coaching, healthcare etc.) the NLP practitioner is trained to use this knowledge to push change from outside, when it’s far more consistent, relevant, accurate and integrous to enable Others to traverse, repair, and integrate the route of their own change; NLP practitioners, like doctors and sales folks, attempt to cause change (obviously using their own personal biases), rather than trusting that people must elicit their own change to remain congruent.

5. Until the system determines how to garner buy-in and consensus in a way that’s congruent with its own rules, and make room for something new in a way the system won’t face disorder, change will be resisted rather than threaten the status quo.

In the late 1980s I discovered the books of Roger Schank who said questions could uncover unconscious criteria. Really? Conventional questions were biased, restricting responses to the bias of the Asker. Since change is an inside job, how could questions enable choice?

I played with this problem for a year and eventually developed a new form of question (Facilitative Question) that uses specific words, in a specific order, in sequenced steps, as an unbiased directional device (much like a GPS, with no bias), giving Outsiders (influencers) the ability to efficiently and congruently help Others traverse the route to change, and make quick decisions and shifts in ways that their system deems tolerable. In other words, a form of question that can be used by doctors, sellers, coaches, leaders – anyone who seeks to enable change in others. An example: ‘How will you know if it’s time to reconsider your hairstyle?’ instead of ‘Why do you wear your hair like that?’ – leading Others directly to the route down their own unconscious change criteria, rather than manipulating the change sought by the Questioner. After all, an Outsider can never fully understand the makeup of someone else’s unique, unconscious system. Why not lead them through to their own change steps?

6. As neutral navigation devices, Facilitative Questions direct the Other’s unconscious down the sequence of change without bias, enabling consensus from the system, congruent to their own norms. In others words, influencers can help people make permanent, congruent change, so long as they eschew leading from their own biases.

Used in sales, coaching, negotiating, leadership, healthcare, decision making, and management, these questions help the Other get straight to the heart of their own decisions, enabling influencers to quickly determine how – or if – to proceed with integrity, collaboration, and authenticity. {In sales, Facilitative Questions quickly eliminate those who would never buy, discover and teach those with a need (initially recoznized or not) AND an ability to buy, and close sales in half the time. Buyers need to take these steps (Pre-Sales) prior to any buying decision anyway, and usually make them behind-the-scenes while sellers wait.}

In the 80s and 90s, I found the books of Benjamin Libet and Maurice Merleau-Ponty who confirmed my early theories that behavior comes from subjective experience. I’ve met with, and read close to a thousand books and papers from, communication experts, behavioral scientists, neuroscientists. I even interviewed for a PhD in Behavioral Sciences, but was told my work was 20 years ahead of the current research at the time so I couldn’t use my own work as my PhD thesis. I did begin an experiment at Columbia with a behavioral scientist on the criteria people used to make decisions with (behavioral vs belief), but our funding got cut as we were set to begin. And in all of my sales/Buying Facilitation® training programs, we have a pilot group compared with a control group.

THE BIRTH OF BUYING FACILITATION®: WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?

Putting all of my learning and ideas together, it presents a very different picture than the one we currently use to influence, lead, or serve others. Here’s a recap.

1. Everyone makes decisions based on their own unique, unconscious subjective biases. External data will be resisted, accepted, misunderstood accordingly, regardless of the need or efficacy of the information.

2. Everyone, and every team, exists within a system of idiosyncratic rules that create and maintain the status quo, and will resist change (buying anything, shifting behaviors) until the system has bought-in to shifting congruently.

3. Conventional questions are biased by the Questioner, and lead to restricted data collection and responses. Facilitative Questions lead the system through it’s own path to assembly, and change management so it can make its own best decisions and discover its own type of Excellence.

4. People can only hear/listen according to the parameters of their internal biases, and will misunderstand, mishear, forget, filter any data that is not aligned. I wrote a book on this: What? Did you really say what I think I heard?

5. Change can only happen from the inside, regardless of the external ‘reality’ or need.

6. Information cannot teach anyone how to make a new decision; all change/choice comes from shifts within the existent, systemic beliefs. Information is only useful once all elements of change are in place; otherwise it gets misheard, misinterpreted, or ignored.

7. Until a system knows how, if, when, where to change congruently, no change will occur regardless of any external reality.

8. It’s possible to facilitate Others through congruent change, be part of their decision making process, potentially expand their choices, and work with those who are ready, willing, and able. This enables influencers to truly serve rather than depend on ‘intuition’ or their own biases.

I know we spend billions creating pitches, rational arguments, data gathering, questionnaires, training, Behavior Modification, etc. But this only captures the low hanging fruit – those who have gotten to the place where new ideas, solutions, training’s fit. People who

- think differently,

- have rules, expectations or beliefs that run counter to the offered information (but can be recalculated), or

- have not yet reached the realization that they need what you’ve got on offer (but do need it)

will either mishear, misunderstand, or resist when presented with any outside push or data. That means we’re offering our solutions before the system is set up for change, finding only the low hanging fruit who have already determined their route to change. Conventional models that push/offer/pull information – rational or otherwise – cannot do better than be there when the fruit’s ready to fall. But by adding some skills that first facilitates change readiness, it’s possible to become part of the decision process and a place on the Buying Decison Team.

My core thinking remains outside of conventional thinking because it’s not academic (although it’s more accepted these days). But after 60 years of study and mistakes, 35 years of training clients and running control groups, I’ve accomplished my childhood goal. My generic facilitation model (Buying Facilitation®) has been taught globally since 1985; it does just what I always wanted to do: offer scalable skills to anyone seeking to truly serve others by facilitating their own brand of excellence. In other words, I can teach influencers to help Others know how, when, if to make new choices for themselves. It’s an unconventional model, and certainly not academic. But it’s been proven with over 100,000 people globally.

These days, I continue to learn, read, study, and theorize. Should anyone in healthcare, sales, leadership, OD, or coaching be interested in learning more, or collaborating, or or or, I’m here.

____________

Sharon Drew Morgen has been coding and teaching change and choice in sales, coaching, healthcare, and leadership for over 30 years. She is the developer of Buying Facilitation®, a generic decision facilitation model used in sales, and is the author of the NYTimes Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity and Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell. Sharon Drew’s book What? Did you really say what I think I heard? has been called a ‘game changer’ in the communication field, and is the first book that explains, and solves, the gap between what’s said and what’s heard. Her assessments and learning tools that accompany the book have been used by individuals and teams to learn to enter conversations able to hear without filters.

Sharon Drew is the author of one of the top 10 global sales blogs with 1700+ articles on facilitating buying decisions through enabling buyers to manage their status quo effectively. To learn Buying Facilitation® contact sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.

Sharon Drew Morgen April 29th, 2019

Posted In: Change Management, Listening, News

Behavior Modification doesn’t modify behaviors: an essay on why it fails and what to use

I recently chatted with a VC invested in 15 healthcare apps that use Behavior Modification to facilitate patients through permanent behavior change for enhanced health. He said although many of his apps use it, there’s no scientific evidence that Behavior Modification works. Hmmmm… And the reason you’re still using it is… “There’s nothing else to use.”

I contend that current Behavior Mod approaches are not only faulty, but seriously harmful to a large population of people who need to consider permanent change. You see, Behavior Modification does NOT instigate new behaviors or permanently change existing ones. In diet, smoking cessation, and exercise maintenance alone, there is a 97% failure rate for ongoing adoption of altered behaviors.

Now let’s be honest here. If you’ve ever tried to keep lost weight off, or habituate a new exercise routine, or stop smoking, or… you’ve probably tried to modify your current behaviors by doing the same thing differently, or doing a different thing the same. Diets always work. It’s when we try to return to ‘normal’ that our lost weight returns. The problem isn’t the diet.

This essay is about conscious behavior change. For this, I must take you to the source – into your brain – to not only understand why you behave the way you do or resist new behaviors, but HOW to actually elicit the behaviors you want. Conventional thinking usually explains the WHAT and WHY, but fail to teach the HOW. In this article I’ll lead you through HOW your brain causes your behaviors, and where the inflexion points are so you can intervene and consciously design your own behaviors (or lead your patients and clients through to their best choices). I’ve tried to make the more procedural stuff fun and relatable so you’ll barely notice. Enjoy.

BEHAVIOR

There are two major problems with Behavior Modification:

1. Behavior 2. Modification.

I suspect most people haven’t considered what a ‘behavior’ denotes. Behaviors are our identity, our beliefs, our history/norms/life experience in action, in the service of representing us to the world, to show people through our actions what we stand for. It’s how we show up as ‘us’ every day – the demonstration, the expression, the translation of who we are – the external actions that portray our internal essence, beliefs, and morals. Like an autobiography is the written representation of a life but not THE life. Like going to church represents us practicing our faith but not FAITH. Behaviors are the visible depictions of each of us.

Behaviors don’t occur without a stimulus. Nor do they operate in a vacuum. And they are always, always congruent with our beliefs. You know, without asking, that someone wearing a bathing suit to a church wedding most likely has different beliefs than the other guests. It’s not about the bathing suit.

In our brains, behaviors are the output of physiological signals, much as words and meaning are the output of our brain’s interpretation of electrical signals coming into our ears. In other words, it’s all happening unconsciously through brain chemistry: behaviors are merely the end result of a very specific sequence of chemical signals in our brains that traverse a series of congruency checks that ultimately agree to act.

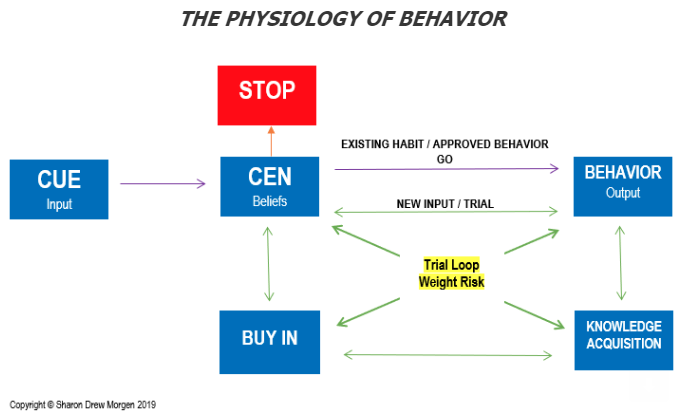

Below is a summary of the physiology of what happens in our brains – the step by step path – that ultimately leads to behaviors. Here you’ll recognize exactly where and why Behavior Mod fails. For those wanting to skip the brain stuff, go directly to the CASE STUDY below. But don’t forget to peek at the great graphic of the HOW of decision making just below.

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF BEHAVIOR

For those of you who love to learn esoteric stuff, here is an overview of the physiology of our brain’s path to a behavior: from an Input/Cue that starts the process and signals that an action is requested, through our filters and trials that check the signal for risk, through to a STOP or an Output/Behavior. It’s what our brain does to cause us to behave, or not.

SIGNAL/CUE/MOTIVATION/INPUT: We start by giving ourselves some sort of CUE, an instruction or request, to take action, whether it’s to brush our teeth, or move our arm, or eat a salad. This signal traverses a neural pathway to get to the next stage, the CEN.

CEN/BELIEF FILTER: Our Central Executive Network, or CEN, filters all requests through our beliefs, morals, and norms. If the incoming cue is congruent with our beliefs and determined to have no risk, we peruse our lifelong history and trillions (literally) of neural pathways to find an existing behavior we’ve used before that matches the request. If one is found, there’s an immediate GO and you get a CUE –> BEHAVIOR, or in other words, INPUT –> OUTPUT match immediately. This happens when you get into your car and automatically put on your seatbelt, for example.

But if the motivating cue is incongruent with our norms and beliefs there is a STOP or resistance. This happens a lot when people try to do something they dislike, like add working out to their schedules, for example, because they believe they should – and they hate the gym, hate working out, and hate taking the time out of their day. Or something they’ve tried and have failed at. Or something that goes against their beliefs.

For the past 10 years, after decades of unsuccessfully trying to convince myself to get to the gym, I finally created a new habit and now go 8 hours a week – AND I HATE THE GYM. First I changed my cue. I told telling myself that as a healthy person, I believed (CEN) I am fit in mind, body, spirit. Now, if I want to be a slug, I ask myself if I want to be a healthy person today. Thankfully, I do 90% of the time.

The job of the CEN is to let in the good stuff and stop the bad. Behavior Mod doesn’t have the ability to change cues, and address belief filters.

TRIAL LOOP: If the CEN is congruent with the signal and there’s no behavior already in place, the signal goes into a trial loop where it

- assigns/weights/determines the risk of the new against the beliefs and norms (CEN);

- seeks new knowledge/learning tools to trial and practice behaviors that conform with the cue;

- while comparing against the filters in the CEN for congruence;

- develop a new neural pathway/synaptic connection for a new behavior if congruent (i.e. GO) or

- STOP a signal if a risk uncovered, and no new behavior is formed.

Obviously our brains are set up to filter out what they believe will harm us. And anything new that has not been bought into, or tested to fit in with our other norms, will be deemed a risk, regardless of the efficacy of the new or need for change.

When our cue gets stopped and doesn’t lead to a behavior it’s because

- We’re giving ourselves a cue that’s incongruent with who we are;

- We’re trying to use a pathway already developed for a different behavior;

- We’re attempting to change a behavior by starting from the output (behavior) end without going through the congruency process of weighting risk and getting Buy In.

Input (signal, cue, stimulus) –> CEN (beliefs) –> trial loop (congruency check) –> output (behavior)

You can see that behaviors are at the end of a chain of physiological events, the final step along the neural pathway between the input cue and action. The end. The response. The reaction. Nowhere do they occur on their own.

THE PROBLEM WITH MODIFICATION

Behavior Mod attempts to effect change at the output where an existing behavior is already in place, hoping that by practicing a preferred behavior over and over and over, different results will emerge. Obviously it can’t work. New behaviors activate and will permanently take hold ONLY once instructed by an input stimulus that has then been approved by your beliefs and weighted for risk and congruence.

In other words, when you try to change a behavior by trying to change an existing behavior, you’re trying to change the output without getting necessary Buy In for change. It’s not even logical. It’s why diets and exercise regimens fail: people try to change their existing habits rather than form wholly new ones with different signals that lead to wholly different – and more successful – routines.

Consider a robot that has been programmed to move forward but you want it to move backward. You tell it why ‘backward’ is best, you pitch it reasons it should want to move backward, you tell it a story about why moving backward is advantageous, and you even try to push it backward. But until you reprogram it, it will not go backward. It’s the same with us. We must create new incoming cues, go through a trial loop that weights risks/tries/fails/tries/fails, gathers necessary data along the way, and gets agreement to develop a wholly new neural pathway to a new action that’s congruent. You cannot change a behavior by changing a behavior.

It’s also impossible to expect permanent change when we omit the entire risk-check element of our Buy In process. The risk to our system of becoming imbalanced by shoving in something foreign into a system that’s been working just fine, is just too great, regardless of the efficacy of the new, and any new inputs will stop behaviors that haven’t been vetted. And Behavior Mod supersedes these tests by trying to push the change from the output end, before it’s been vetted.

HOW TO CHANGE BEHAVIORS PERMANENTLY

Here are three of the key elements involved in how we choose to behave differently. It’s systemic.

SYSTEMS CONGRUENCE. The role of systems here cannot be underestimated because they’re the glue that holds us together. I am a system. You are a system. Your family is a system. Every conglomeration of things that follow the same rules is a system. Every system has its own status quo – its own unique set of norms, beliefs, identifiers that show up, together, and are identified as Me, or My Family, or My Work Team. The system of people working together at Google will be different from the system of people working together at Kaiser Permanente, with unspoken rules that apply to dress codes, hiring practices, working hours, relationships, the way meetings are run.

The job of our status quo is to maintain Systems Congruence (You learned that in 6th grade. It means that all systems, all of us, seek balance, or Homeostasis.) so we can wake up every day being who we were yesterday. And all day, trillions of signals enter into our brains and lead us to behaviors that have met the criteria of systems congruence and safety. These are our habits. Indeed, our brains check all incoming signals for incongruence before behaviors are agreed to, making sure we remain in balance minutely.

Any time you try (and try and try and…) to behave in a way that unconsciously causes imbalance within you – when you push against an existing habit or action and try to get a different behavior – you’ll experience resistance or sabotage. For any proposed change, to maintain congruence, your system must agree, Buy In, in a way that matches your beliefs, identity, and norms. And it’s physiologic, chemical, automatic, and unconscious. Our brains do this for us every second of our lives. Behavior Modification supersedes this process, trying to induce behavior change in a way that risks generating imbalance, or Systems Incongruence – and inaction.

INPUT. Any new input signals will only become a behavior if they are congruent with the beliefs, identity and norms of the person’s system. When you wish to change a behavior, it’s necessary to input the correct message as all that follows is a response to the input cue. I recently asked a friend with a long history of trying to lose weight permanently what she tells herself to begin (her stimulus). ‘I tell myself I’m a disgusting slob.’ Since different inputs will be assessed by the CEN uniquely and each achieve different outputs, being a ‘disgusting slob’ will invite the same behaviors that caused her to be a ‘disgusting slob’ to begin with, and she’ll fail over and over; she’s inputting the same signal expecting a different response, but her brain will only seek/find the old response.

TRIAL LOOP. Because a new input seeking a new output/behavior demands a congruence test in the CEN to assess risk, there’s a trial process that includes

- adding new knowledge (education, books, coaching, lessons, etc.) to achieve new skills to trial;

- continual comparisons against the CEN, or against our beliefs and identity, as each iteration progresses, to test for congruence;

- Buy-In so our CEN, our beliefs and identity, concur with each iteration of trialing and failing as our brains go about weighting any risk;

- trialing any new behaviors for congruence, that result from adding the new knowledge.

If at any point a risk is determined to put the system out of congruence, it will stop the new behavior. If the input cue is determined safe, it will agree to create a new behavior. Not to kick a dead horse, but Behavior Mod does not address this at all. That’s why it fails so often.

So if my friend wanted to permanently lose weight, she’d input something like “I’m a healthy person”, discover which of her beliefs are connected to that (“As part of my health practice, I eat nutritionally healthful food that works well with my lifestyle.”), and go through a trial loop that would include her doing research and possibly blood tests to see what types of food best align with her being healthy, and end up with a new set of healthful eating behaviors. Ultimately she’d have a lifetime food plan that kept her healthy, congruent with her beliefs about herself and habituated into her life. And her eating would become part of her system and become habituated.

CASE STUDY

I’ll share a recent experience I had using this process with my neighbor. In it I’ll label each element within the Buy In process in the chart above.

My neighbor Maria once came to my house crying. Her doctor had told her she was borderline diabetic and needed to eat differently. He gave her a printed list of foods to eat and foods to avoid and sent her on her way. At my house she told me she’d been trying for months, lost some weight, but finally gave up and went back to her normal eating habits and gained back the weight. But she was fearful of dying from diabetes like her mother did. Apparently the fear of death wasn’t enough to change her eating habits. She asked if I could help, and I told her I’d lead her through to finding her own answers. Here was our exchange.

SDM: Who are you? [RESPONSE TO DOCTOR INPUT/CUE]

Maria: I’m a mother and grandmother. [CEN FILTER, IDENTITY]

SDM: What are your beliefs that go with being a mother and grandmother?

Maria: I believe I’m responsible for feeding my family in a way that makes them happy. [CEN FILTER, BELIEFS]

SDM: What is it you’re doing now that makes them happy? [CEN FILTER, IDENTITY]

Maria: I make 150 tortillas each morning and hand them out to all my children and grandchildren who come over on their way to work and school in the morning. They love my tortillas. But I know they’re bad for me with all the lard in them, even though I eat them. I’ve tried to stop, but since I’m making them for everyone, they are a big part of my diet. When the doctor told me I can’t eat them anymore, it felt like he asked me to not love my family. [NO BUY IN FROM CEN/STOP]

SDM: So I hear that tortillas are the way you keep your family happy but the lard in them is unhealthy for you. Is there any other way you can keep your family happy by feeding them without putting your own health at risk?

Maria: Hmmmm… I could make them corn tacos. They don’t have lard, and my family loves them. [TRIAL LOOP, BUY-IN]

Maria then invited her entire (huge) family for dinner and presented her daughter Sonia with her tortilla pan outfitted with a big red bow. [TRIAL LOOP, NEW BEHAVIOR] She told her family she couldn’t make tortillas any more due to health reasons, and proclaimed Sonia the new “Tortilla Tia”. She could, she said, make them corn tacos whenever they wanted and she would happily try out whatever they wanted so long as they were happy. [TRIAL LOOP, KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION]

That simple switch in her food choices and her handover to Sonia helped her begin a healthy eating plan. It inspired her to research other food substitutions [TRIAL LOOP, KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION] she could make to avoid having a chronic illness. Eventually, she lost weight and had a food plan more closely aligned with what her doc suggested. And of course, she could still make her family happy with her food and meet her beliefs. [NEW NEURAL PATHWAY, NEW BEHAVIOR]

As you can see, just from entering the problem with a different hat on – helping patients figure out their own route to change and Buy In instead of trying to drive it – using a different curiosity and a different questioning system, it’s quite possible to guide people to discover their own best choices that are congruent with who they are.

FACILITATE BUY IN THEN ADD BEHAVIOR MOD

I realize my ideas aren’t in the mainstream at the moment. But just because Behavior Mod has such a stronghold in the healthcare field doesn’t mean it can’t be reexamined or appended. And just because Behavior Mod has been the accepted model to induce change doesn’t mean it’s successful. Remember when we believed top down leadership was the way to go? Millions of books sold? Billions spent on consultants? I’m offering something new here that deserves consideration.

And it’s not either/or; it can be both/and. You don’t have to throw away what you’ve got, just add a front end to stimulate Buy In. I’ve used this approach to train a large number of sales folks globally to facilitate buying decisions and it was quite successful. And here’s an article I wrote on adding my change facilitation concepts to Behavior Mod, should you have interest.

There are plenty of uses for this add on. Think of enabling patient Buy In for obesity or cardio clinics, to help patients design a work-out regimen for heart health. Or for diabetes sufferers to design a healthful food plan for life. Or athletes trying to change an inferior swing, or develop a new pattern to their feet differently to run faster. What about helping yourself meditate daily or organizing your life. Or to get more sleep.

We can help people alter their behaviors in a way that’s not only congruent with who they are, but helps them make their own best choices. But not with Behavior Modification alone.

Contact me to put you on an advance list for a Buy In program I’m running in June with Learning Strategies. In it you’ll learn how to design your own flow chart from Cue to Behavior to have conscious choice whenever you want to make a change. And if you have any interest at all in testing this model, or just sharing ideas, I welcome the conversation. sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com.

______________

Sharon Drew Morgen is an original thinker and thought leader. She is the author of 9 books, including the New York Times Business Bestseller Selling with Integrity, and the Amazon bestsellers Dirty Little Secrets: why buyers can’t buy and sellers can’t sell, and What? Did you really say what I think I heard? She is also the inventor of the Buying Facilitation® model which is used by sellers, leaders, and coaches, to facilitate others through all of the steps of their decision making and change to lead them through their steps to purchase or change. Sharon Drew is a trainer, coach, speaker, and consultant in the areas of sales, healthcare, leadership, and coaching. sharondrew@sharondrewmorgen.com

Sharon Drew Morgen February 18th, 2019

Posted In: Communication, Listening

Starting a Tech Company in 1983

I started up a tech company in London in 1983. I never meant to. And I certainly didn’t know what I was doing.

I was brought across the pond by a tech company as a sales director. But after a few days and a few conversations with my husband Ben (brought over by the same company to do contract tech work), I realized there was a far greater opportunity than just selling services for the first Fourth Generation Language (4GL) Database Management software FOCUS we supported: programming support, of course. But what about users? Since it was a user-focused tool, and users weren’t techies, I envisioned two problems: they might not have the knowledge to cull, organize and manage their data; they might not have the skills to communicate effectively with the techies they had to collaborate with. (As a non-techie married to a techie, I was well aware of the communication challenges of different types of brains.) What if we could be a decision support group that provided a broad range of services for users?

I somehow convinced my new manager to let me ‘go’ with my ideas. But truth be told, I didn’t know what I was talking about. That wasn’t a problem: because I think in systems, I had a high-level understanding of the problems but none of the details. In other words, I understood the structure but not the content (and it’s always easy to find the right content once you’ve got the structure). Never occurred to me I wouldn’t succeed.

None of us were smart enough to know what we didn’t know, although they must have known something: I became their most successful group, bringing in 142% of the gross profit of their 5 companies. Me? I ended up an entrepreneur, starting a tech group (which became its own company) in two countries (UK, Germany), with no experience; making a whole bunch of money for me and my investors; serving a large, diverse client base; traveling extensively around Europe; having full expression of my creativity; and living in London. But it didn’t start that way.

As I share my experiences, I’d like you to consider that this was the early 1980s: there was no internet, no Google, no email, and no websites with phone numbers and names. It was necessary, in general, to call Information to get a phone number, and they needed the address before they gave you the number. True story. Computers weren’t even used for much – think Commodore, with floppys; Macs weren’t even introduced until 1984; Google not until 1996. So in the pre-internet,pre-information age, selling and marketing were decidedly different than today. And yet I found a way, in a country strange to me, in an industry I knew nothing about, selling a product I didn’t understand, to be quite successful. Just a bit of old-timee caring, trust, and integrity. Let me begin.

WHAT I DIDN’T KNOW

I’d never been an entrepreneur. With only 5 years as a successful salesperson (and 12 years prior as a social worker and journalist), I had no idea what ‘business’ meant. In fact, I didn’t know:

- How to hire anyone.

- How to find anyone – to hire, to sell to.

- The rules: of tech, London, business, corporate politics, start-ups. Nothin’.

- What was going on in the field, what the field was comprised of, the nature of my competition.

- What I was selling – what my service provided, what it did differently than my competition.

- What clients needed, how they took care of the problems without my solution, why they would buy anything rather than keep doing what they were doing.

- How to explain, pitch, or present what I was selling (because I didn’t understand it).

- How to run a business – the jobs needing to be done, how they got apportioned.

- How to manage staff; how to recognize when I needed to hire/fire staff.

- What success or failure looked like and how to know in advance if either was happening.

- How to put together a budget, how much money I needed to run a company (I didn’t know I could run on a loss, so I thought I’d need to earn money before spending it.)

- Expectations, time frames, problems, problem resolutions.

I was ignorant. But I did understand people, systems, structure, hard work, risk-taking, communication, and integrity. And I knew who, what, and why to trust. I was on my way.

I began in a tiny, tiny office (Obviously once a closet, it was so narrow I had to move the chair so the door would open; the ‘desk’ was a plank of wood attached to the wall.) in a group office space. I sat, that first day, and stared at a British phone not even knowing how to dial out or get Information. I had to hire people, obviously. But for what? And how did I find them? I had to get revenue, but from who? This was in 1983 before the ‘tech’ boom. No one knew what was going on; I had no one to even ask these questions to.

Should I start selling first to bring in revenue? or hire support staff? Should I hire techies to go into client environments – for when I made a sale? But how could I hire anyone before I knew what prospective clients needed? What criteria should I use to hire techies – since the 4GL was for users, techies needed both tech skills and people skills, no? What percentage of each was necessary? How would I know what to pay them?

It was a conundrum. I couldn’t pay anyone until I was getting revenue; I couldn’t get revenue until I got clients; I couldn’t get clients until I had people to do their work. Where to begin? I could design a path forward once I figured out the elements. And as I later realized, starting with no expectations, no biases, no knowledge, and no comparators, was a blessing. I was given a clear road on which to travel, using any means of transport I could develop within a miasma of confusion, to get wherever I wanted to go. Best fun ever.

EMPLOYEES RUNNING THE COMPANY

I took on all the tasks concurrently: afternoons interviewing techies and hiring staff, mornings on sales calls. I decided to be my own salesperson so I could learn the components of the underlying system and understand the full range of givens going forward. I needed to know where I was at so I could get where I was going. (Did you ever try to get directions when you didn’t know the address where you were?)

I solved the ‘which comes first’ problem by initially hiring contract techies (who I later made permanent). This also solved my cash flow issue so I needn’t lay out money until I landed a client. But who was a good hire? I had Ben design a tech test I could score myself using an overlay with answers; I personally added some client service questions to understand their people skills. Between this test and the interview, I knew exactly the pluses and minuses of each person.

To hire staff, I had to determine the job scope and potential outcome that each hire would offer, certainly hard to do when I had no way of knowing what jobs were necessary; it was a year before we realized we needed a training group, for example. So I made a lot of (mostly good but not always) guesses. Before our interviews, I told prospective hires to determine how much they wanted to earn (I trusted people knew how much they were worth; I sure didn’t.) bring a P&L (Someone said I needed that. No idea what it was.) to the interview with a plan to illustrate how they could earn their salary, cover their costs, and make a profit. The ones who came in with creative ideas were hired. I didn’t know until years later what a crazy idea this was. But not that crazy, turned out.

Since I didn’t know the difference between a cost center and a profit center, I hadn’t realized ‘obvious’ things, like you can’t make Reception a profit center. But I didn’t know I couldn’t, so I did. A bit more about that in a moment. Suffice it to say, by making each person their own profit center, everybody ran their own companies and became wholly committed to being successful because that’s how they got paid. Plus they were having such fun creating. Sounds silly now, but it worked: I hired people who wanted to be creative, take responsibility, and work from the same parameters of ‘excellence’ that I wanted the company to exemplify:

- Take whatever risks you deem necessary, so long as you stay within the parameters of integrity and have a good shot at succeeding.

- Always trust clients, care for their well-being, never never never lie.

- Always do what you say you’ll do.

- Never leave clients compromised, regardless of time or situation. And always stay on top of how clients are doing.

- If you’re going to fail, tell me before you fall so I can get involved; if you are already failing, there’s nothing I can do but watch you fall. Note: my team always, always told be well before a potential failure, and together we always fixed the impending disaster. We didn’t mind making mistakes.

- I don’t believe in giving people X weeks vacation. If you’re running your own company, you take the time off as needed to be healthy, creative, and happy. Ultimately, I had to pry folks from their seats to get them to take time off. Sometimes I had to call their wives (and they were all men, except the sales team), tell them to send the kids to Grandma, and keep the tired husbands in bed for a few days. I even sent meals to the house so no one had to cook. This small thing alone kept my folks loyal enough to not take other job offers of twice the salary. I really cared about them.

So now I knew how to hire staff and techies when I needed them. But that was the tip of the iceberg.

SELLING AN UNKNOWN

Because I had a successful history of taking on challenges without knowing anything, I didn’t think twice about selling something I didn’t understand. And truly, although I had very general knowledge, I knew nothing of the specifics – what I was selling, who used it, the need for it, or the buying environment for it. I didn’t even know how to get phone numbers or company names (1983, remember? No Google, no information ‘online’. Think about it.). Reception gave me a phone book to look up American companies that I knew had offices in London and who possibly might be using FOCUS. But it was all a guess; I was flying blind. My first call was to the Receptionist at American Express:

SDM: Hi. I wonder if you could help me. This is a sales call, and I have a product that will help the folks using a new Fourth Generation Language get better reports. But I’m new in London, and new in the business, and haven’t a clue what groups are using this or who to ask for. Do you have any ideas for me?

REC: Interesting. I’ll give you the names of a few group heads and you can call and see if they fit. If these don’t work, call me back and I’ll keep digging. My name is Ann.

First on her list was Jim. No idea what he did or his title; I just had a name and extension number.

SDM: Hi Jim. My name is Sharon Drew Morgen. Ann gave me your name and suggested you were a good person to speak with but neither of us was sure. This is a sales call. I’m selling support services for the Fourth Generation Language FOCUS, and I wonder if you’re using the language or need any help. Is this a good time?

JIM: How refreshing! Thanks for telling me it’s a sales call. Can you tell me more about what you offer (No idea.) because we are using FOCUS but because it’s so new I don’t know what I don’t know (Hahahaha. That made two of us).

SDM: (I was in trouble here. My only option was to keep putting the focus on him.): I have an idea. Rather than me tell you what I can do for you, tell me exactly how you’re currently using the software, what your target goal is and if you’re reaching it, where you’re not, and I’ll put it all together in my head (with Ben’s help!) and see if there is anything I can do to support you, then get back to you if I can. I do have a curiosity: what’s stopping you from knowing more than you do about using the software to its fullest capability? (This was curious to me. As a systems thinker, I always want to know the parameters of any problem. What was going on that Jim didn’t know them?)

JIM: Wow. I should know more, right? Let me tell you how I’m using it (and so began my learning!) and we can schedule another call once you’ve had time to think. And if you don’t mind, I’m going to give you the names and phone numbers of my colleagues so we can all be on the same page here. I also havea friend at DEC with the same problems I’m having, so I’ll give you his number as well. I suspect you can help us all.

And so began my journey to success. Helping people figure out how to take care of their own needs first, and then helping where I could add something, was so much easier than pitching what I thought would be meaningful, especially since I had no earthly idea how to discuss a product I didn’t yet have.

GROWING THE COMPANY WITH PEOPLE

I soon began selling contract services for systems engineers, programmers, project leaders, and managers. When visiting them in the field at their new jobs, I began to understand the ‘need’ not only for technical support but as I had originally guessed, for ‘communication management’ within their teams and with the users who had no clue how to manage or direct techies. I quickly realized that merely putting techies into client teams wouldn’t keep the core communication issues, inherent in this first report tool, at bay.

I needed to hire someone with tech skills, communication skills, and people skills. A tall order that few could do. But unless someone could take that on, I could foresee plenty of innate problems that could crop up and cause fires and lost time and business.

Thankfully, I found John to hire as a ‘Make Nice Guy’. John had it all; I paid him a fortune (around $100,000, which in 1984 was a huge salary – just about broke the bank) and gave him this job description:

- Make sure the code in every program, on every client site, is good so there are no systems failures. A shut down at any time of day or night, at any site, would be his to fix;

- Make sure our techies fit into the client teams and the relationships were smooth. If our techies stayed in their position for the length of the contract John got a bonus;

- Make sure the client is happy, and check to see if they need additional help on other teams;

- Find other groups on client sites bringing in FOCUS before the vendor sent in their own contract team. (I had a team already sitting and waiting to begin as the vendor implemented the new software before they even pitched their consulting services.)

- And oh – take as much holiday time you need, so long as I have no fires.

I never wanted my phone to ring with problems; I had a company to grow. John’s job was to run all operations. And he was so good at everything that our projects almost always got done ahead of schedule and under budget, causing clients to keep us around for far longer than the initial contract as their trust grew. And because we were so reliable, clients began giving us whole projects to do on our own, freeing up their own people for more creative work. We were in Bose, British Airways, Amdahl, DEC, for years, causing me to hire more and more tech staff. We grew to about 43 techies in under 4 years. And there was very little ‘beach’ time.

I had very high criteria around keeping staff happy; without them, I didn’t have a business. Since so many folks were in the field and I couldn’t see them regularly, I called each and every techie at least once a month to check in, discuss birthdays and holidays, share gossip. I offered current staff a new job opening before seeking anyone from outside to fill it. I let them trial the job for 3 weeks, and if they wanted it and we all agreed, it was theirs. And because I thought it important that those in the field didn’t feel isolated, once a month I treated the whole team of techies and staff to a darts night with a few pints at a local pub. I always lost. I still can’t play darts.

As we grew, my growing group of employees were coming up with their own ideas, certainly better than mine. One of the running jokes became the ability to get me to say “WE’RE DOING WHAT?????” When I said those words, someone would gleefully shout out, “SHE SAID IT! SHE SAID IT!” It was never little stuff either. They sure took risks.

SDM: Hey Harold. Nice seeing you. I’ve not seen you for days. Where’ve you been?

HAROLD: We needed to expand our training programs so I was scouting out new venues. I’m just getting ready to sign a contract to rent about 1000 feet of space in an adjoining office.

SDM: WE’RE DOING WHAT????”

Damn if he didn’t rock out. He’d put together user training, tech training, and even a manager training that he somehow got me to teach (I’M TEACHING WHAT????). Harold figured that since I did such a good job managing techies with no technical experience myself, I could teach user managers how to work with techies. He was right. And it was a very popular program. Who knew!? All I had to do was do what I was told.

The other prominent wish I heard from the managers was an admonishment: “Please, please don’t sell anything we don’t have today please!” Yeah, right. As a salesperson, I always can think of things I can sell someone when I hear what I think is a need. And once I knew how flexible our services were, I could promise something could be delivered. Immediately.

STAFF PERSON SEEING MY FACE AS I RETURNED TO MY OFFICE: She’s done it again!!

SDM: [as the team hustled into my office, arms crossed, scowling, knowing]: I couldn’t help it. Sorry guys. It’s not a big deal. We only need to do X. Won’t be bad.

STAFF: And when did you promise we’d deliver this?

SDM: Monday.

STAFF: BUT IT’S WEDNESDAY!!!!! We’ll need to work all weekend!!!! My wife will kill me!!!!

SDM: I’ll run the Xerox machine, keep you in Pizza and Coke, edit while you’re writing. I’ll buy the beer! I’ll help you!

And so we stayed up to the minute in our offerings and program designs and had a steady flow of new solutions. What a blast we had, albeit a missed birthday or two. Sorry kids.

One more fun thing. The technical training guy wanted to be able to see into the work the students were doing at their desks and correct their errors from his front computer. He needed a computer with a large screen, capable of connecting to, and viewing, multiple computers at once. You might shrug at this now, but in 1985, no one had ever heard of such a thing. Julian made a bazillion calls and actually found a man in Amsterdam to come over, raise our training room floor to organize all the cables, and built Julian the computer he wanted. Done and done.

THE PROFIT CENTER RECEPTION AREA

I promised you this story. And it’s quite wonderful. Shows what can happen when you really trust your staff.

I hired a woman named Anne-Marie as the receptionist. She had run a car dealership and was accustomed to dealing with aggressive men, without an ounce of need for any social relationships.

Anne-Marie’s pitch to me during our interview for the job of Receptionist was that she wanted a percentage of our net profits (and this was in 1984!); for this, she would create an environment run like a well-oiled machine, with everyone intent on taking care of customers with nothing getting in the way. I didn’t know what that meant; I just trusted her.

She was imposing in every way: very tall – about 6 feet – and wore very tidy, officious, crisp suits. She wore bright red, severe lipstick; she walked with lowered eyes, with a sort of strut; her brown hair was tied up in some 1920s hairstyle that increased our perception that she knew what she was doing. And I can’t say often enough that she was terrifying. It was like having a dictator around all the time, watching, watching. We did whatever she said. Seriously. No one, no one, messed with her. We didn’t even want to find out what the ‘or else’ was.

Anne-Marie figured out what needed to be done within a month on the job. As the person in the front, Anne-Marie overheard staff gossiping about each other, obviously taking time away from their work and her profit; she noticed phones being unanswered, which didn’t serve customers; she overheard people saying they ‘didn’t know’ something, which didn’t serve customers either. She wasn’t having it.

She put us to work. EVERY DAY Anne-Marie made us write up what was going on with our clients, problems with our job and caseload, our conflicts with each other. We had to leave these pages on her desk before we left at night, and she would come in early and distribute them by 7:00 A.M. She wanted everyone to have all the knowledge necessary to serve clients and each other, every day.

She called these things TOADS. Take what you want and destroy…. I don’t remember what the blasted acronym was, but trust me, I still have nightmares. Those bloody TOADS. We hated them. EVERY DAY we all had to stay an extra hour at night to write the damn things – and remember, there were no computers and many of the staff couldn’t type on the typewriters, so mostly we wrote them by hand. Pages. They went on for pages. And in addition to staying late EVERY NIGHT to write the dratted things, we had to come in early every day to read the ten or twelve sets of TOADS that Anne-Marie left on our desks from our teammates. One of the things I did when designing our new offices was to install glass walls so we could all see each other (Open plan offices weren’t a Thing yet.). We would glumly look up from our writing at 6:30 or so at night, see each other sitting there writing, give each other grim smiles, chuckle, and put our heads back down to write. We suffered together.